Posterior vaginal prolapse (rectocele)

Overview

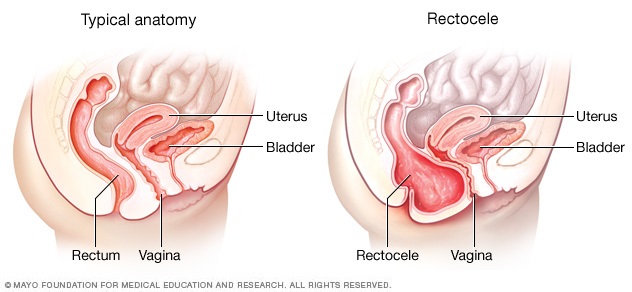

A posterior vaginal prolapse is a bulge of tissue into the vagina. It happens when the tissue between the rectum and the vagina weakens or tears. This causes the rectum to push into the vaginal wall. Posterior vaginal prolapse is also called a rectocele (REK-toe-seel).

Childbirth-related tears, chronic straining to pass stool (constipation) and other activities that put pressure on pelvic tissues can lead to posterior vaginal prolapse. A small prolapse might not cause symptoms.

With a large prolapse, you might notice a bulge of tissue that pushes through the opening of the vagina. To pass stool, you might need to support the vaginal wall with your fingers. This is called splinting. The bulge can be uncomfortable, but it's rarely painful.

If needed, self-care measures and other nonsurgical options are often effective. For severe posterior vaginal prolapse, you might need surgery to fix it.

A posterior vaginal prolapse, also known as a rectocele, occurs when the wall of tissue that separates the rectum from the vagina weakens or tears. When this happens, tissues or structures just behind the vaginal wall — in this case, the rectum — can bulge into the vagina.

Symptoms

A small posterior vaginal prolapse (rectocele) might cause no symptoms.

Otherwise, you may notice:

- A soft bulge of tissue in the vagina that might come through the opening of the vagina

- Trouble having a bowel movement

- Feeling pressure or fullness in the rectum

- A feeling that the rectum has not completely emptied after a bowel movement

- Sexual concerns, such as feeling embarrassed or sensing looseness in the tone of the vaginal tissue

Many women with posterior vaginal prolapse also have prolapse of other pelvic organs, such as the bladder or uterus. A surgeon can evaluate the prolapse and talk about options for surgery to fix it.

When to see a doctor

Sometimes, posterior vaginal prolapse doesn't cause problems. But moderate or severe posterior vaginal prolapses might be uncomfortable. See a health care provider if your symptoms affect your day-to-day life.

Causes

Posterior vaginal prolapse results from pressure on the pelvic floor or trauma. Causes of increased pelvic floor pressure include:

- Birth-related tears

- Forceps or operative vaginal deliveries

- Long-lasting constipation or straining with bowel movements

- Long-lasting cough or bronchitis

- Repeated heavy lifting

- Being overweight

Pregnancy and childbirth

The muscles, ligaments and connective tissue that support the vagina stretch during pregnancy, labor and delivery. This can make those tissues weaker and less supportive. The more pregnancies you have, the greater your chance of developing posterior vaginal prolapse.

If you've only had cesarean deliveries, you're less likely to develop posterior vaginal prolapse. But you still could develop the condition.

Risk factors

Anyone with a vagina can develop posterior vaginal prolapse. However, the following might increase the risk:

- Genetics. Some people are born with weaker connective tissues in the pelvic area. This makes them naturally more likely to develop posterior vaginal prolapse.

- Childbirth. Having vaginally delivered more than one child increases the risk of developing posterior vaginal prolapse. Tears in the tissue between the vaginal opening and anus (perineal tears) or cuts that make the opening of the vagina bigger (episiotomies) during childbirth might also increase risk. Operative vaginal deliveries, and forceps specifically, increase the risk of developing this condition.

- Aging. Growing older causes loss of muscle mass, elasticity and nerve function, which causes muscles to stretch or weaken.

- Obesity. Extra body weight places stress on pelvic floor tissues.

Prevention

To help keep posterior vaginal prolapse from getting worse, you might try to:

- Perform Kegel exercises regularly. These exercises can strengthen pelvic floor muscles. This is especially important after having a baby.

- Treat and prevent constipation. Drink plenty of fluids and eat high-fiber foods, such as fruits, vegetables, beans and whole-grain cereals.

- Avoid heavy lifting and lift correctly. Use your legs instead of your waist or back to lift.

- Control coughing. Get treatment for a chronic cough or bronchitis, and don't smoke.

- Avoid weight gain. Ask your health care provider to help you determine the best weight for you. Ask for advice on how to lose weight, if needed.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of posterior vaginal prolapse often happens during a pelvic exam of the vagina and rectum.

The pelvic exam might involve:

- Bearing down as if having a bowel movement. Bearing down might cause the prolapse to bulge, revealing its size and location.

- Tightening pelvic muscles as if stopping a stream of urine. This test checks the strength of the pelvic muscles.

You might fill out a questionnaire to assess your condition. Your answers can tell your health care provider about how far the bulge extends into the vagina and how much it affects your quality of life. This information helps guide treatment decisions.

Rarely, you might need an imaging test:

- MRI or an X-ray can determine the size of the tissue bulge.

- Defecography is a test to check how well your rectum empties. The procedure combines the use of a contrasting agent with an imaging study, such as X-ray or MRI.

Treatment

Treatment depends on how severe your prolapse is. Treatment might involve:

- Observation. If the posterior vaginal prolapse causes few or no symptoms, simple self-care measures — such as performing Kegel exercises to strengthen pelvic muscles — might give relief.

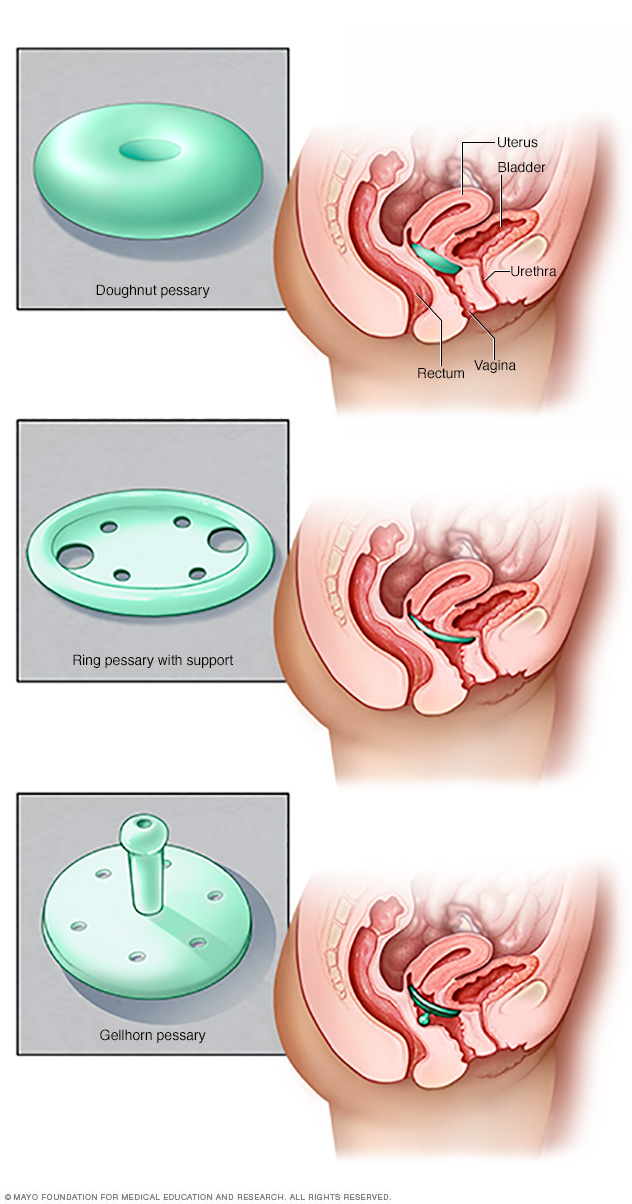

- Pessary. A vaginal pessary is a silicone device that you put into the vagina. The device helps support bulging tissues. A pessary must be removed regularly for cleaning.

Surgery

Surgery to fix the prolapse might be needed if:

- Pelvic floor strengthening exercises or using a pessary doesn't control your prolapse symptoms well enough.

- Other pelvic organs are prolapsed along with the rectum, and your symptoms really bother you. Surgery to fix each prolapsed organ can be done at the same time.

Surgery often involves removing extra, stretched tissue that forms the vaginal bulge. Then stitches are placed to support pelvic structures. When the uterus is also prolapsed, the uterus might need to be removed (hysterectomy). More than one type of prolapse can be repaired during the same surgery.

Pessaries come in many shapes and sizes. The device fits into the vagina and provides support to vaginal tissues displaced by pelvic organ prolapse. A health care provider can fit a pessary and help provide information about which type would work best.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Sometimes, self-care measures provide relief from prolapse symptoms. You could try to:

- Perform Kegel exercises to strengthen pelvic muscles

- Avoid constipation by eating high-fiber foods, drinking plenty of fluids and, if needed, taking a fiber supplement

- Avoid bearing down during bowel movements

- Avoid heavy lifting

- Control coughing

- Achieve and maintain a healthy weight

Kegel exercises

Kegel exercises strengthen pelvic floor muscles. A strong pelvic floor provides better support for pelvic organs. It also might relieve bulge symptoms that posterior vaginal prolapse can cause.

To perform Kegel exercises:

- Find the right muscles. To find your pelvic floor muscles, try stopping urine midstream when you use the toilet. Once you know where these muscles are, you can practice these exercises. You can do the exercises in any position, although you might find it easiest to do them lying down at first.

- Perfect your technique. To do Kegels, imagine you are sitting on a marble and tighten your pelvic muscles as if you're lifting the marble. Try it for three seconds at a time, then relax for a count of three.

- Maintain your focus. For best results, focus on tightening only your pelvic floor muscles. Be careful not to flex the muscles in your abdomen, thighs or buttocks. Avoid holding your breath. Instead, breathe freely during the exercises.

- Repeat three times a day. Aim for at least three sets of 10 to 15 repetitions a day.

Kegel exercises may be most successful when they're taught by a physical therapist or nurse practitioner and reinforced with biofeedback. Biofeedback uses monitoring devices to let you know that you're tightening the right set of muscles in the right way.

Preparing for an appointment

For posterior vaginal prolapse, you might need to see a doctor who specializes in female pelvic floor conditions. This type of doctor is called a urogynecologist.

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms and when they began

- All medicines, vitamins and supplements you take, including doses

- Key personal and medical information, including other conditions, recent life changes and stressors

- Questions to ask your health care provider

For posterior vaginal prolapse, some basic questions to ask your care provider include:

- What can I do at home to ease my symptoms?

- Should I restrict any activities?

- What are the chances that the bulge will grow if I don't do anything?

- What treatment approach do you think would be best for me?

- What are the chances that my condition will come back after I have surgery?

- What are the risks of surgery?

Be sure to ask any other questions that occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your health care provider

Your provider is likely to ask you a number of questions, including:

- Do you have pelvic pain?

- Do you ever leak urine?

- Have you had a severe or ongoing cough?

- Do you do any heavy lifting in your job or daily activities?

- Do you strain during bowel movements?

- Has anyone in your family ever had pelvic organ prolapse or other pelvic problems?

- How many children have you given birth to? Were your deliveries vaginal?

- Do you plan to have children in the future?

Last Updated Aug 10, 2022

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use