Aplastic anemia

Overview

Aplastic anemia is a condition that occurs when your body stops producing enough new blood cells. The condition leaves you fatigued and more prone to infections and uncontrolled bleeding.

A rare and serious condition, aplastic anemia can develop at any age. It can occur suddenly, or it can come on slowly and worsen over time. It can be mild or severe.

Treatment for aplastic anemia might include medications, blood transfusions or a stem cell transplant, also known as a bone marrow transplant.

Symptoms

Aplastic anemia can have no symptoms. When present, signs and symptoms can include:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Rapid or irregular heart rate

- Pale skin

- Frequent or prolonged infections

- Unexplained or easy bruising

- Nosebleeds and bleeding gums

- Prolonged bleeding from cuts

- Skin rash

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Fever

Aplastic anemia can be short-lived, or it can become chronic. It can be severe and even fatal.

Causes

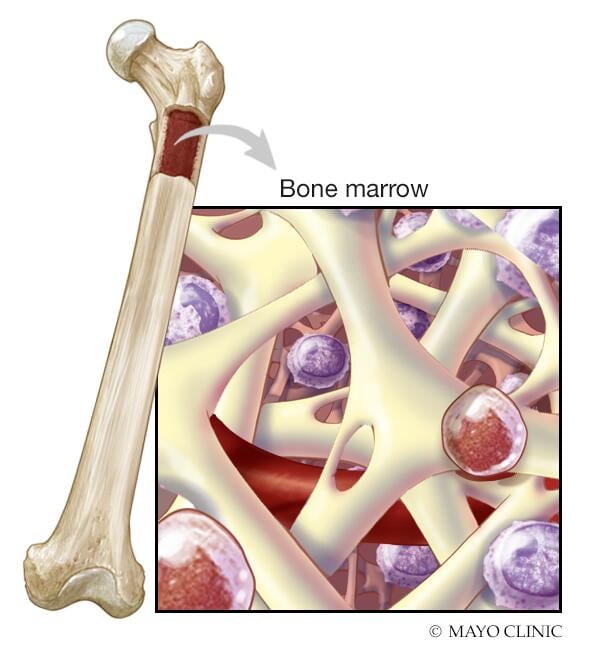

Stem cells in the bone marrow produce blood cells — red cells, white cells and platelets. In aplastic anemia, stem cells are damaged. As a result, the bone marrow is either empty (aplastic) or contains few blood cells (hypoplastic).

The most common cause of aplastic anemia is from your immune system attacking the stem cells in your bone marrow. Other factors that can injure bone marrow and affect blood cell production include:

- Radiation and chemotherapy treatments. While these cancer-fighting therapies kill cancer cells, they can also damage healthy cells, including stem cells in bone marrow. Aplastic anemia can be a temporary side effect of these treatments.

- Exposure to toxic chemicals. Toxic chemicals, such as some used in pesticides and insecticides, and benzene, an ingredient in gasoline, have been linked to aplastic anemia. This type of anemia might improve if you avoid repeated exposure to the chemicals that caused your illness.

- Use of certain drugs. Some medications, such as those used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and some antibiotics, can cause aplastic anemia.

- Autoimmune disorders. An autoimmune disorder, in which your immune system attacks healthy cells, might involve stem cells in your bone marrow.

- A viral infection. Viral infections that affect bone marrow can play a role in the development of aplastic anemia. Viruses that have been linked to aplastic anemia include hepatitis, Epstein-Barr, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19 and HIV.

- Pregnancy. Your immune system might attack your bone marrow during pregnancy.

- Unknown factors. In many cases, doctors aren't able to identify the cause of aplastic anemia (idiopathic aplastic anemia).

Connections with other rare disorders

Some people with aplastic anemia also have a rare disorder known as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, which causes red blood cells to break down too soon. This condition can lead to aplastic anemia, or aplastic anemia can evolve into paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Fanconi's anemia is a rare, inherited disease that leads to aplastic anemia. Children born with it tend to be smaller than average and have birth defects, such as underdeveloped limbs. The disease is diagnosed with the help of blood tests.

Risk factors

Aplastic anemia is rare. Factors that can increase risk include:

- Treatment with high-dose radiation or chemotherapy for cancer

- Exposure to toxic chemicals

- The use of some prescription drugs — such as chloramphenicol, which is used to treat bacterial infections, and gold compounds used to treat rheumatoid arthritis

- Certain blood diseases, autoimmune disorders and serious infections

- Pregnancy, rarely

Prevention

There's no prevention for most cases of aplastic anemia. Avoiding exposure to insecticides, herbicides, organic solvents, paint removers and other toxic chemicals might lower your risk of the disease.

Diagnosis

The following tests can help diagnose aplastic anemia:

- Blood tests. Normally, red blood cell, white blood cell and platelet levels stay within certain ranges. In aplastic anemia all three of these blood cell levels are low.

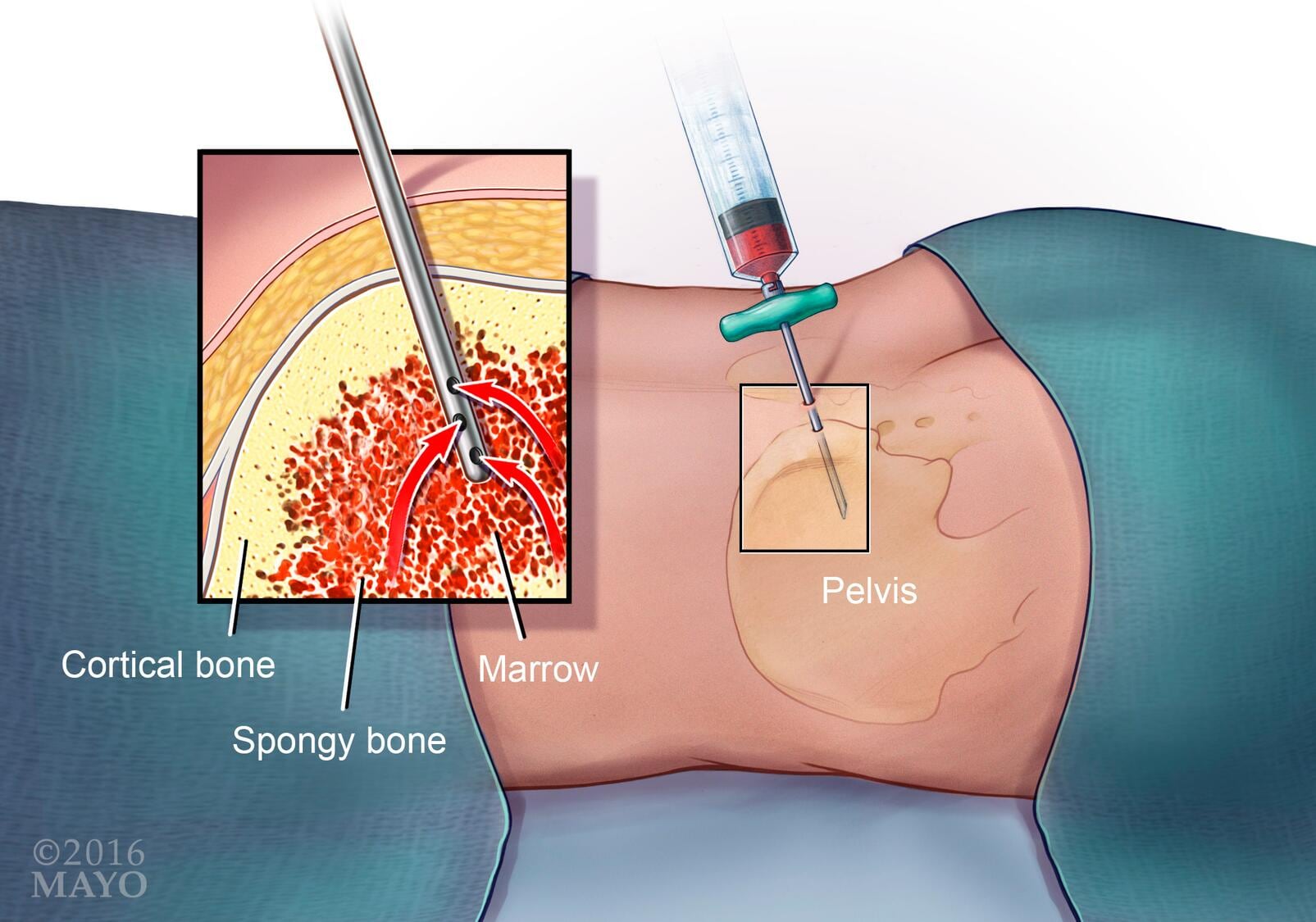

- Bone marrow biopsy. A doctor uses a needle to remove a small sample of bone marrow from a large bone in your body, such as your hipbone. The sample is examined under a microscope to rule out other blood-related diseases. In aplastic anemia, bone marrow contains fewer blood cells than normal. Confirming a diagnosis of aplastic anemia requires a bone marrow biopsy.

Once you've received a diagnosis of aplastic anemia, you might need other tests to determine the cause.

Treatment

Treatments for aplastic anemia, which will depend on the severity of your condition and your age, might include observation, blood transfusions, medications, or bone marrow transplantation. Severe aplastic anemia, in which your blood cell counts are extremely low, is life-threatening and requires immediate hospitalization.

Blood transfusions

Although not a cure for aplastic anemia, blood transfusions can control bleeding and relieve symptoms by providing blood cells your bone marrow isn't producing. You might receive:

- Red blood cells. These raise red blood cell counts and help relieve anemia and fatigue.

- Platelets. These help prevent excessive bleeding.

While there's generally no limit to the number of blood transfusions you can have, complications can sometimes arise with multiple transfusions. Transfused red blood cells contain iron that can accumulate in your body and can damage vital organs if an iron overload isn't treated. Medications can help rid your body of excess iron.

Over time your body can develop antibodies to transfused blood cells, making them less effective at relieving symptoms. The use of immunosuppressant medication makes this complication less likely.

Stem cell transplant

A stem cell transplant to rebuild the bone marrow with stem cells from a donor might be the only successful treatment option for people with severe aplastic anemia. A stem cell transplant, also called a bone marrow transplant, is generally the treatment of choice for people who are younger and have a matching donor — most often a sibling.

If a donor is found, your diseased bone marrow is first depleted with radiation or chemotherapy. Healthy stem cells from the donor are filtered from the blood. The healthy stem cells are injected intravenously into your bloodstream, where they migrate to the bone marrow cavities and begin creating new blood cells.

The procedure requires a lengthy hospital stay. After the transplant, you'll receive drugs to help prevent rejection of the donated stem cells.

A stem cell transplant carries risks. Your body may reject the transplant, leading to life-threatening complications. In addition, not everyone is a candidate for transplantation or can find a suitable donor.

Immunosuppressants

For people who can't undergo a bone marrow transplant or for those whose aplastic anemia is due to an autoimmune disorder, treatment can involve drugs that alter or suppress the immune system (immunosuppressants).

Drugs such as cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune) and anti-thymocyte globulin suppress the activity of immune cells that are damaging your bone marrow. This helps your bone marrow recover and generate new blood cells. Cyclosporine and anti-thymocyte globulin are often used together.

Corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone (Medrol, Solu-Medrol), are often used with these drugs.

Although effective, these drugs further weaken your immune system. It's also possible for anemia to return after you stop these drugs.

Bone marrow stimulants

Certain drugs — including colony-stimulating factors, such as sargramostim (Leukine), filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta), epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit), and eltrombopag (Promacta) — help stimulate the bone marrow to produce new blood cells. Growth factors are often used with immune-suppressing drugs.

Antibiotics, antivirals

Having aplastic anemia weakens your immune system, which leaves you more prone to infections.

If you have aplastic anemia, see your doctor at the first sign of infection, such as a fever. You don't want the infection to get worse, because it could prove life-threatening. If you have severe aplastic anemia, your doctor might prescribe antibiotics or antiviral medications to help prevent infections.

Other treatments

Aplastic anemia caused by radiation and chemotherapy treatments for cancer usually improves after those treatments stop. The same is true for most other drugs that induce aplastic anemia.

Pregnant women with aplastic anemia are treated with blood transfusions. For many women, pregnancy-related aplastic anemia improves once the pregnancy ends. If that doesn't happen, treatment is still necessary.

Self care

If you have aplastic anemia, take care of yourself by:

- Resting when you need to. Anemia can cause fatigue and shortness of breath with even mild exertion. Take a break and rest when you need to.

- Avoiding contact sports. Because of the risk of bleeding associated with a low platelet count, avoid activities that can cause a cut or fall.

- Protecting yourself from germs. Wash your hands frequently and avoid sick people. If you develop a fever or other indicators of an infection, see your doctor for treatment.

Coping and support

Tips to help you and your family better cope with your illness include:

- Research your disease. The more you know, the better prepared you'll be to make treatment decisions.

- Ask questions. Be sure to ask your doctor about anything related to your disease or treatment that you don't understand. It might help you to record or write down what your doctor tells you.

- Be vocal. Don't be afraid to express your concerns to your doctor or other health care professionals treating you.

- Seek support. Ask family and friends for emotional support. Ask them to consider becoming blood donors or bone marrow donors. It might help to talk to others coping with the disease. Ask your doctor if he or she knows of local support groups, or contact the Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation. It offers a peer support network and can be reached at 800-747-2820.

- Take care of yourself. Proper nutrition and sleep are important to optimize blood production.

Preparing for your appointment

Start by making an appointment with your primary care doctor. He or she might then refer you to a doctor who specializes in treating blood disorders (hematologist). If aplastic anemia comes on suddenly, your treatment might begin in the emergency room.

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms and when they began

- Key personal information, including any recent life changes, such as a new job, particularly one that exposes you to chemicals

- Medications, vitamins and other supplements you take, including doses

- Questions to ask your doctor

Take a family member or a friend with you to your doctor, if possible, to help you remember the information you're given.

For aplastic anemia, questions to ask your doctor include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Are there other possible causes for my symptoms?

- What's my prognosis?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend?

- Are there alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- I have another health condition. How can I best manage them together?

- Do you have brochures or other printed material I can have? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor is likely to ask you questions, such as:

- Have you had recent infections?

- Have you bled unexpectedly?

- Are you more tired than usual?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- Does anything appear to worsen your symptoms?

Last Updated Feb 11, 2022

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use