Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection

Overview

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection occurs when H. pylori bacteria infect your stomach. This usually happens during childhood. A common cause of stomach ulcers (peptic ulcers), H. pylori infection may be present in more than half the people in the world.

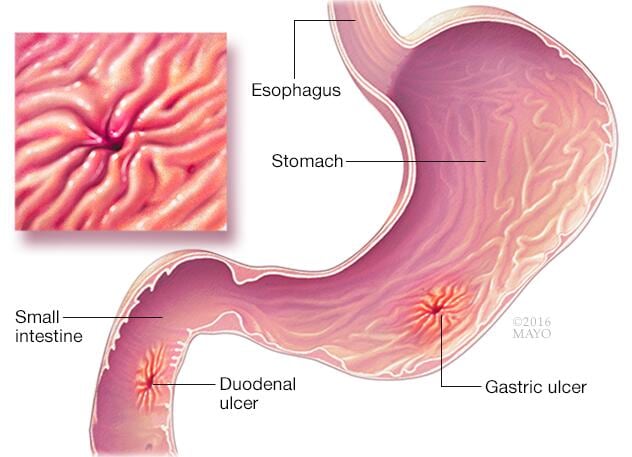

Most people don't realize they have H. pylori infection because they never get sick from it. If you develop signs and symptoms of a peptic ulcer, your health care provider will probably test you for H. pylori infection. A peptic ulcer is a sore on the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the first part of the small intestine (duodenal ulcer).

H. pylori infection is treated with antibiotics.

Symptoms

Most people with H. pylori infection will never have any signs or symptoms. It's not clear why many people don't have symptoms. But some people may be born with more resistance to the harmful effects of H. pylori.

When signs or symptoms do occur with H. pylori infection, they are typically related to gastritis or a peptic ulcer and may include:

- An ache or burning pain in your stomach (abdomen)

- Stomach pain that may be worse when your stomach is empty

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Frequent burping

- Bloating

- Unintentional weight loss

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your health care provider if you notice any signs and symptoms that may be gastritis or a peptic ulcer. Seek immediate medical help if you have:

- Severe or ongoing stomach (abdominal) pain that may awaken you from sleep

- Bloody or black tarry stools

- Bloody or black vomit or vomit that looks like coffee grounds

Causes

H. pylori infection occurs when H. pylori bacteria infect your stomach. H. pylori bacteria are usually passed from person to person through direct contact with saliva, vomit or stool. H. pylori may also be spread through contaminated food or water. The exact way H. pylori bacteria causes gastritis or a peptic ulcer in some people is still unknown.

Risk factors

People often get H. pylori infection during childhood. Risk factors for H. pylori infection are related to living conditions in childhood, such as:

- Living in crowded conditions. Living in a home with many other people can increase your risk of H. pylori infection.

- Living without a reliable supply of clean water. Having a reliable supply of clean, running water helps reduce the risk of H. pylori.

- Living in a developing country. People living in developing countries have a higher risk of H. pylori infection. This may be because crowded and unsanitary living conditions may be more common in developing countries.

- Living with someone who has an H. pylori infection. You're more likely to have H. pylori infection if you live with someone who has H. pylori infection.

Complications

Complications associated with H. pylori infection include:

- Ulcers. H. pylori can damage the protective lining of the stomach and small intestine. This can allow stomach acid to create an open sore (ulcer). About 10% of people with H. pylori will develop an ulcer.

- Inflammation of the stomach lining. H. pylori infection can affect the stomach, causing irritation and swelling (gastritis).

- Stomach cancer. H. pylori infection is a strong risk factor for certain types of stomach cancer.

Prevention

In areas of the world where H. pylori infection and its complications are common, health care providers sometimes test healthy people for H. pylori. Whether there is a benefit to testing for H. pylori infection when you have no signs or symptoms of infection is controversial among experts.

If you're concerned about H. pylori infection or you think you may have a high risk of stomach cancer, talk to your health care provider. Together you can decide whether you may benefit from H. pylori testing.

Diagnosis

Several tests and procedures are used to determine whether you have H. pylori infection. Testing is important for detection of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Repeat testing after treatment is important to be sure H. pylori is gone. Tests may be done using a stool sample, through a breath test and by an upper endoscopy exam.

Stool tests

- Stool antigen test. This is the most common stool test to detect H. pylori. The test looks for proteins (antigens) associated with H. pylori infection in the stool.

- Stool PCR test. A lab test called a stool polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test can detect H. pylori infection in stool. The test can also identify mutations that may be resistant to antibiotics used to treat H. pylori. However, this test is more expensive than a stool antigen test and may not be available at all medical centers.

Breath test

During a breath test — called a urea breath test — you swallow a pill, liquid or pudding that contains tagged carbon molecules. If you have H. pylori infection, carbon is released when the solution comes in contact with H. pylori in your stomach.

Because your body absorbs the carbon, it is released when you breathe out. To measure the release of carbon, you blow into a bag. A special device detects the carbon molecules. This test can be used for adults and for children over 6 years old who are able to cooperate with the test.

Scope test

A health care provider may conduct a scope test, known as an upper endoscopy exam. Your provider may perform this test to investigate symptoms that may be caused by conditions such as a peptic ulcer or gastritis that may be due to H. pylori.

For this exam, you'll be given medication to help you relax. During the exam, your health care provider threads a long, flexible tube with a tiny camera (endoscope) attached down your throat and esophagus and into your stomach and the first part of the intestine (duodenum). This instrument allows your provider to view any problems in your upper digestive tract. Your provider may also take tissue samples (biopsy). These samples are examined for H. pylori infection.

Because this test is more invasive than a breath or stool test, it's typically done to diagnose other digestive problems along with H. pylori infection. Health care providers may use this test for additional testing and to look for other digestive conditions. They may also use this test to determine exactly which antibiotic may be best to treat H. pylori infection, especially if the first antibiotics tried didn't get rid of the infection.

This test may be repeated after treatment, depending on what is found at the first endoscopy or if symptoms continue after H. pylori infection treatment.

Testing considerations

Antibiotics can interfere with the accuracy of testing. In general, retesting is done only after antibiotics have been stopped for four weeks, if possible.

Acid-suppressing drugs known as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) can also interfere with the accuracy of these tests. It's possible acid-suppressing drugs known as histamine (H-2) blockers may also interfere with the accuracy of these tests. Depending on what medications you're taking, you'll need to stop taking them, if possible, for up to two weeks before the test. Your health care provider will give you specific instructions about your medications.

The same tests used for diagnosis can be used to tell if H. pylori infection is gone. If you were previously diagnosed with H. pylori infection, you'll generally wait at least four weeks after you complete your antibiotic treatment to repeat these tests.

Treatment

H. pylori infections are usually treated with at least two different antibiotics at once. This helps prevent the bacteria from developing a resistance to one particular antibiotic.

Treatment may also include medications to help your stomach heal, including:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These drugs stop acid from being produced in the stomach. Some examples of PPIs are omeprazole (Prilosec), esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid) and pantoprazole (Protonix).

- Bismuth subsalicylate. More commonly known by the brand name Pepto-Bismol, this drug works by coating the ulcer and protecting it from stomach acid.

- Histamine (H-2) blockers. These medications block a substance called histamine, which triggers acid production. One example is cimetidine (Tagamet HB). H-2 blockers are only prescribed for H. pylori infection if PPIs can't be used.

Repeat testing for H. pylori at least four weeks after your treatment is recommended. If the tests show the treatment didn't get rid of the infection, you may need more treatment with a different combination of antibiotics.

Preparing for your appointment

See your health care provider if you have signs or symptoms that indicate a complication of H. pylori infection. Your provider may test and treat you for H. pylori infection, or refer you to a specialist who treats diseases of the digestive system (gastroenterologist).

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment, and what to expect.

What you can do

At the time you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as restrict your diet.

Also, preparing a list of questions to ask may help you make the most of your time with your health care provider. Questions to ask may include:

- How did H. pylori infection cause the complications I'm experiencing?

- Can H. pylori cause other complications?

- What kinds of tests do I need?

- Do these tests require any special preparation?

- What treatments are available?

- What treatments do you recommend?

- How will I know if the treatment worked?

Ask any additional questions that occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Does anything make them better or worse?

- Have your parents or siblings ever experienced similar problems?

- What medications or supplements do you take regularly?

- Do you take any over-the-counter pain relievers such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve)?

Being ready to provide information and answer questions may allow more time to cover other points you want to discuss.

Last Updated May 5, 2022

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use