Bronchiolitis

Overview

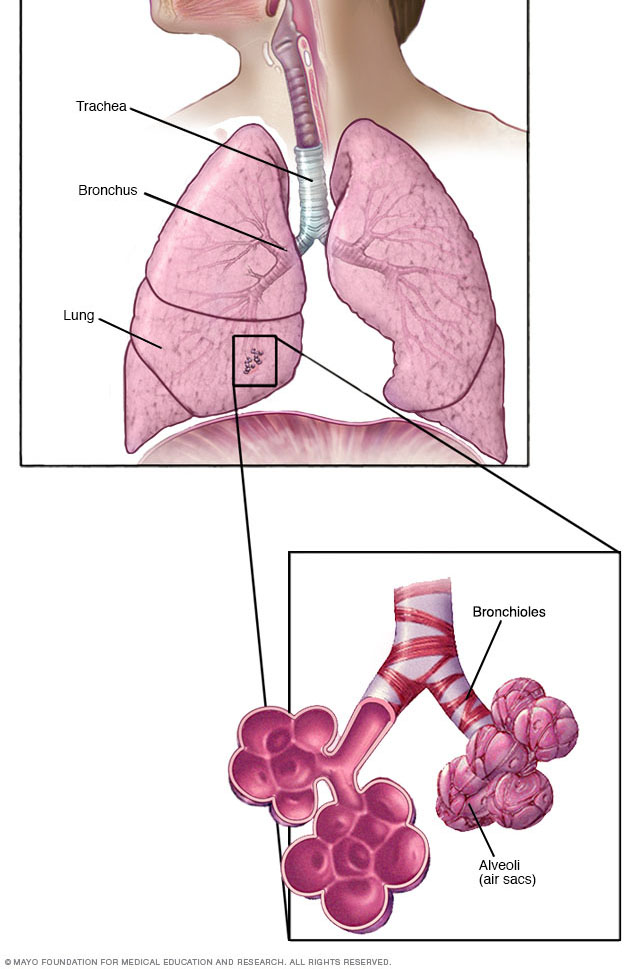

Bronchiolitis is a common lung infection in young children and infants. It causes swelling and irritation and a buildup of mucus in the small airways of the lung. These small airways are called bronchioles. Bronchiolitis is almost always caused by a virus.

Bronchiolitis starts out with symptoms much like a common cold. But then it gets worse, causing coughing and a high-pitched whistling sound when breathing out called wheezing. Sometimes children have trouble breathing. Symptoms of bronchiolitis can last for 1 to 2 weeks but occasionally can last longer.

Most children get better with care at home. A small number of children need a stay in the hospital.

In your lungs, the main airways, called bronchi, branch off into smaller and smaller passageways. The smallest airways, called bronchioles, lead to tiny air sacs called alveoli.

Symptoms

For the first few days, the symptoms of bronchiolitis are much like a cold:

- Runny nose.

- Stuffy nose.

- Cough.

- Sometimes a slight fever.

Later, your child may have a week or more of working harder than usual to breathe, which may include wheezing.

Many infants with bronchiolitis also have an ear infection called otitis media.

When to see a doctor

If symptoms become serious, call your child's health care provider. This is especially important if your child is younger than 12 weeks old or has other risk factors for bronchiolitis — for example, being born too early, also called premature, or having a heart condition.

Get medical attention right away if your child has any of these symptoms:

- Has blue or gray skin, lips and fingernails due to low oxygen levels.

- Struggles to breathe and can't speak or cry.

- Refuses to drink enough, or breathes too fast to eat or drink.

- Breathes very fast — in infants this can be more than 60 breaths a minute — with short, shallow breaths.

- Can't breathe easily and the ribs seem to suck inward when breathing in.

- Makes wheezing sounds when breathing.

- Makes grunting noises with each breath.

- Appears slow moving, weak or very tired.

Causes

Bronchiolitis happens when a virus infects the bronchioles, which are the smallest airways in the lungs. The infection makes the bronchioles swollen and irritated. Mucus collects in these airways, which makes it difficult for air to flow freely in and out of the lungs.

Bronchiolitis is usually caused by the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV is a common virus that infects just about every child by 2 years of age. Outbreaks of RSV infection often happen during the colder months of the year in some locations or the rainy season in others. A person can get it more than once. Bronchiolitis also can be caused by other viruses, including those that cause the flu or the common cold.

The viruses that cause bronchiolitis are easily spread. You can get them through droplets in the air when someone who is sick coughs, sneezes or talks. You also can get them by touching shared items — such as dishes, doorknobs, towels or toys — and then touching your eyes, nose or mouth.

Risk factors

Bronchiolitis usually affects children under the age of 2 years. Infants younger than 3 months have the highest risk of getting bronchiolitis because their lungs and their ability to fight infections aren't yet fully developed. Rarely, adults can get bronchiolitis.

Other factors that increase the risk of bronchiolitis in infants and young children include:

- Being born too early.

- Having a heart or lung condition.

- Having a weakened immune system. This makes it hard to fight infections.

- Being around tobacco smoke.

- Contact with lots of other children, such as in a child care setting.

- Spending time in crowded places.

- Having siblings who go to school or get child care services and bring home the infection.

Complications

Complications of severe bronchiolitis may include:

- Low oxygen in the body.

- Pauses in breathing, which is most likely to happen in babies born too early and in babies under 2 months old.

- Not being able to drink enough liquids. This can cause dehydration, when too much body fluid is lost.

- Not being able to get the amount of oxygen needed. This is called respiratory failure.

If any of these happen, your child may need to be in the hospital. Severe respiratory failure may require that a tube be guided into the windpipe. This helps your child breathe until the infection improves.

Prevention

Because the viruses that cause bronchiolitis spread from person to person, one of the best ways to prevent infection is to wash your hands often. This is especially important before touching your baby when you have a cold, flu or other illness that can be spread. If you have any of these illnesses, wear a face mask.

If your child has bronchiolitis, keep your child at home until the illness is past to avoid spreading it to others.

To help prevent infection:

- Limit contact with people who have a fever or cold. If your child is a newborn, especially a premature newborn, avoid being around people with colds. This is especially important in the first two months of life.

- Clean and disinfect surfaces. Clean and disinfect surfaces and items that people often touch, such as toys and doorknobs. This is especially important if a family member is sick.

- Wash hands often. Frequently wash your own hands and those of your child. Wash with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. Keep an alcohol-based hand sanitizer handy to use when you're away from home. Make sure it contains at least 60% alcohol.

- Cover coughs and sneezes. Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue. Throw away the tissue. Then wash your hands. If soap and water aren't available, use a hand sanitizer. If you don't have a tissue, cough or sneeze into your elbow, not your hands.

- Use your own drinking glass. Don't share glasses with others, especially if someone in your family is ill.

- Breastfeed, when possible. Respiratory infections are less common in breastfed babies.

Immunizations and medicines

In the U.S., respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children who are less than a year old. Two options for immunization can help prevent young infants from getting severe RSV. Both are recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and others.

You and your healthcare professional should discuss which option is best to protect your child:

- Antibody product called nirsevimab (Beyfortus). This antibody product is a single-dose shot given in the month before or during RSV season. It's for newborn babies and those younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season. In the U.S., the RSV season typically is November through March, but it varies in Florida, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam and other U.S. Pacific Island territories.

- Nirsevimab also should be given to children 8 months through 19 months old who are at higher risk of severe RSV disease through their second RSV season. Higher risk conditions include:

- Children with active chronic lung disease from being born too soon (prematurely).

- Children with a severely weakened immune system.

- Children with severe cystic fibrosis.

- American Indian or Alaska Native children.

- Vaccine for pregnant people. The FDA approved an RSV vaccine called Abrysvo for pregnant people to prevent RSV in infants from birth through 6 months of age. A single-dose shot of Abrysvo can be given sometime from 32 weeks through 36 weeks of pregnancy during September through January in the U.S. Abrysvo is not recommended for infants or children.

In rare situations, when nirsevimab is not available or a child is not eligible for it, another antibody product called palivizumab may be given. But palivizumab requires monthly shots given during the RSV season, while nirsevimab is only one shot. Palivizumab is not recommended for healthy children or adults.

Other viruses can cause bronchiolitis too. These include COVID-19 and influenza or flu. Getting seasonal COVID-19 and flu shots every year is recommended for everyone older than 6 months.

Diagnosis

Your child's health care provider can usually diagnose bronchiolitis by the symptoms and listening to your child's lungs with a stethoscope.

Tests and X-rays are not usually needed to diagnose bronchiolitis. But your child's provider may recommend tests if your child is at risk of severe bronchiolitis, if symptoms are getting worse or if the provider thinks there may be another problem.

Tests may include:

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray can show if there are signs of pneumonia.

- Viral testing. A sample of mucus from your child's nose can be used to test for the virus causing bronchiolitis. This is done using a swab that's gently inserted into the nose.

- Blood tests. Occasionally, blood tests might be used to check your child's white blood cell count. An increase in white blood cells is usually a sign that the body is fighting an infection. A blood test also can show if the level of oxygen in your child's bloodstream is low.

Your child's provider may look for symptoms of dehydration, especially if your child has been refusing to drink or eat or has been vomiting. Signs of dehydration include dry mouth and skin, extreme tiredness, and making little or no urine.

Treatment

Bronchiolitis usually lasts for 1 to 2 weeks but symptoms occasionally last longer. Most children with bronchiolitis can be cared for at home with comfort measures. It's important to be alert for problems with breathing that are getting worse. For example, struggling for each breath, not being able to speak or cry because of struggling to breathe, or making grunting noises with each breath.

Because viruses cause bronchiolitis, antibiotics — which are used to treat infections caused by bacteria — don't work against viruses. Bacterial infections such as pneumonia or an ear infection can happen along with bronchiolitis. In this case, your child's health care provider may give an antibiotic for the bacterial infection.

Medicines called bronchodilators that open the airways don't seem to help bronchiolitis, so they usually aren't given. In severe cases, your child's health care provider may try a nebulized albuterol treatment to see if it helps. During this treatment, a machine creates a fine mist of medicine that your child breathes into the lungs.

Oral corticosteroid medicines and pounding on the chest to loosen mucus, a treatment called chest physiotherapy, have not been shown to be effective for bronchiolitis and are not recommended.

Hospital care

A small number of children may need a stay in the hospital. Your child may receive oxygen through a face mask to get enough oxygen into the blood. Your child also may get fluids through a vein to prevent dehydration. In severe cases, a tube may be guided into the windpipe to help breathing.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Though it may not be possible to shorten the length of your child's illness, you may be able to make your child more comfortable. Here are some tips:

- Humidify the air. If the air in your child's room is dry, a cool-mist humidifier or vaporizer can moisten the air. This may help loosen mucus and lessen coughing. Be sure to keep the humidifier clean so that bacteria and molds don't grow in the machine.

- Give your child liquids to stay hydrated. Infants should have formula or breast milk only. Your child's health care provider may add oral rehydration therapy. Older kids can drink whatever they want, such as water, juice or milk, as long as they're drinking. Your child may drink more slowly than usual because of swelling and mucus in the nose. Offer small amounts of liquid often.

- Try saline nose drops to ease stuffiness. You can buy these drops without a prescription. They are effective, safe and won't irritate the nose, even for children. Put several drops into the opening on one side of the nose, called the nostril, then bulb suction that nostril right away. Be careful not to push the bulb too far into the nose. Repeat the same steps in the other nostril.

- Consider pain relievers that you can buy without a prescription. For treatment of fever or pain, ask your child's health care provider about giving your child infants' or children's over-the-counter fever and pain medicines such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, others). Those are safer than aspirin. Aspirin is not recommended in children due to the risk of Reye's syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. Children and teenagers recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms should never take aspirin, as they have a higher risk of Reye's syndrome.

- Avoid secondhand smoke. Smoke can worsen symptoms of respiratory infections. If a family member smokes, ask them to smoke outside of the house and outside of the car.

Don't use other over-the-counter medicines, except for fever reducers and pain relievers, to treat coughs and colds in children under 6 years old. Also, consider avoiding the use of these medicines for children younger than 12 years old. The risks to children outweigh the benefits.

Preparing for an appointment

You're likely to start by seeing your child's primary care provider or pediatrician. Here's some information to help you get ready for the appointment.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms your child has, including any that may not seem related to a cold or flu, and when they started.

- Key personal information, such as if your child was born prematurely or has a heart or lung problem or a weakened immune system.

- Questions to ask your provider.

Questions to ask your provider may include:

- What is likely causing my child's symptoms? Are there other possible causes?

- Does my child need any tests?

- How long do symptoms usually last?

- Can my child spread this infection to others?

- What treatment do you recommend?

- What are other options to the treatment you're recommending?

- Does my child need medicine? If so, is there a generic option to the medicine you're recommending?

- What can I do to make my child feel better?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you suggest?

Feel free to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your child's health care provider may ask questions, such as:

- When did your child first begin having symptoms?

- Does your child have symptoms all the time, or do they come and go?

- How severe are your child's symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to make your child's symptoms better?

- What, if anything, seems to make your child's symptoms worse?

Preparing for questions will help you make the most of your time with your child's health care provider.

Last Updated May 4, 2024

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use