Celiac disease

Overview

Celiac disease is an illness caused by an immune reaction to eating gluten. Gluten is a protein found in foods containing wheat, barley or rye.

If you have celiac disease, eating gluten triggers an immune response to the gluten protein in your small intestine. Over time, this reaction damages your small intestine's lining and prevents it from absorbing nutrients, a condition called malabsorption.

The intestinal damage often causes symptoms such as diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, bloating or anemia. It also can lead to serious complications if it is not managed or treated. In children, malabsorption can affect growth and development in addition to gastrointestinal symptoms.

There's no definite cure for celiac disease. But for most people, following a strict gluten-free diet can help manage symptoms and help the intestines heal.

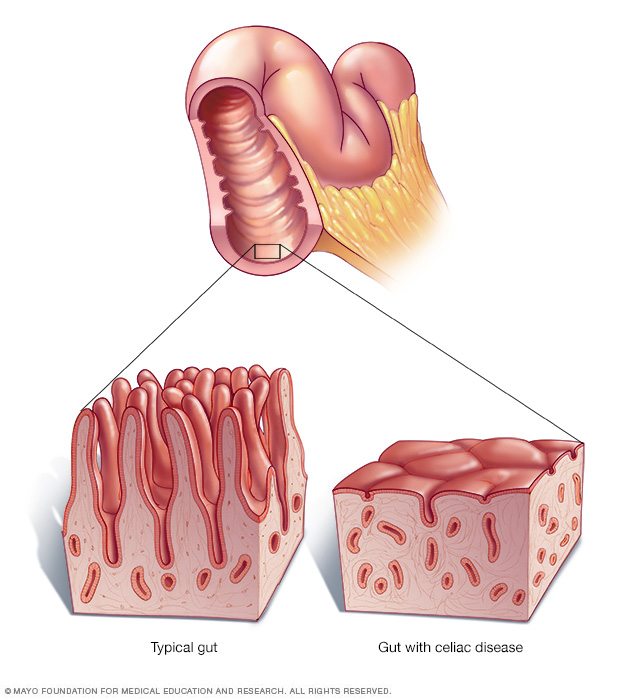

Your small intestine is lined with tiny hairlike projections called villi, which absorb sugars, fats, proteins, vitamins, minerals and other nutrients from the food you eat. Gluten exposure in people with celiac disease damages the villi, making it hard for the body to absorb nutrients necessary for health and growth.

Symptoms

The symptoms of celiac disease can vary greatly. They also may be different in children and adults. Digestive symptoms for adults include:

- Diarrhea.

- Fatigue.

- Weight loss.

- Bloating and gas.

- Abdominal pain.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Constipation.

However, more than half the adults with celiac disease have symptoms that are not related to the digestive system, including:

- Anemia, usually from iron deficiency due to decreased iron absorption.

- Loss of bone density, called osteoporosis, or softening of bones, called osteomalacia.

- Itchy, blistery skin rash, called dermatitis herpetiformis.

- Mouth ulcers.

- Headaches and fatigue.

- Nervous system injury, including numbness and tingling in the feet and hands, possible problems with balance, and cognitive impairment.

- Joint pain.

- Reduced functioning of the spleen, known as hyposplenism.

- Elevated liver enzymes.

Children

Children with celiac disease are more likely than adults to have digestive problems, including:

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Chronic diarrhea.

- Swollen belly.

- Constipation.

- Gas.

- Pale, foul-smelling stools.

The inability to absorb nutrients might result in:

- Failure to thrive for infants.

- Damage to tooth enamel.

- Weight loss.

- Anemia.

- Irritability.

- Short stature.

- Delayed puberty.

- Neurological symptoms, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities, headaches, lack of muscle coordination and seizures.

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Gluten intolerance can cause this blistery skin disease. The rash usually occurs on the elbows, knees, torso, scalp or buttocks. This condition is often associated with changes to the lining of the small intestine identical to those of celiac disease, but the skin condition might not cause digestive symptoms.

Health care professionals treat dermatitis herpetiformis with a gluten-free diet or medicine, or both, to control the rash.

When to see a doctor

Consult your health care team if you have diarrhea or digestive discomfort that lasts for more than two weeks. Consult your child's health care team if your child:

- Is pale.

- Is irritable.

- Is failing to grow.

- Has a potbelly.

- Has foul-smelling, bulky stools.

Be sure to consult your health care team before trying a gluten-free diet. If you stop or even reduce the amount of gluten you eat before you're tested for celiac disease, you can change the test results.

Celiac disease tends to run in families. If someone in your family has the condition, ask a member of your health care team if you should be tested. Also ask about testing if you or someone in your family has a risk factor for celiac disease, such as type 1 diabetes.

Causes

Your genes, combined with eating foods with gluten and other factors, can contribute to celiac disease. However, the precise cause isn't known. Infant-feeding practices, gastrointestinal infections and gut bacteria may contribute, but these causes have not been proved. Sometimes celiac disease becomes active after surgery, pregnancy, childbirth, viral infection or severe emotional stress.

When the body's immune system overreacts to gluten in food, the reaction damages the tiny, hairlike projections, called villi, that line the small intestine. Villi absorb vitamins, minerals and other nutrients from the food you eat. If your villi are damaged, you can't get enough nutrients, no matter how much you eat.

Risk factors

Celiac disease tends to be more common in people who have:

- A family member with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis.

- Type 1 diabetes.

- Down syndrome, William syndrome or Turner syndrome.

- Autoimmune thyroid disease.

- Microscopic colitis.

- Addison's disease.

Complications

Celiac disease that is not treated can lead to:

- Malnutrition. This occurs if your small intestine can't absorb enough nutrients. Malnutrition can lead to anemia and weight loss. In children, malnutrition can cause slow growth and short stature.

- Bone weakening. In children, malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D can lead to a softening of the bone, called osteomalacia or rickets. In adults, it can lead to a loss of bone density, called osteopenia or osteoporosis.

- Infertility and miscarriage. Malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D can contribute to reproductive issues.

- Lactose intolerance. Damage to your small intestine might cause you abdominal pain and diarrhea after eating or drinking dairy products that contain lactose. Once your intestine has healed, you might be able to tolerate dairy products again.

- Cancer. People with celiac disease who don't maintain a gluten-free diet have a greater risk of developing several forms of cancer, including intestinal lymphoma and small bowel cancer.

- Nervous system conditions. Some people with celiac disease can develop conditions such as seizures or a disease of the nerves to the hands and feet, called peripheral neuropathy.

Nonresponsive celiac disease

Some people with celiac disease don't respond to what they consider to be a gluten-free diet. Nonresponsive celiac disease is often due to contamination of the diet with gluten. Working with a dietitian can help you learn how to avoid all gluten.

People with nonresponsive celiac disease might have:

- Bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine.

- Microscopic colitis.

- Poor pancreas function, known as pancreatic insufficiency.

- Irritable bowel syndrome.

- Difficulty digesting sugar found in dairy products (lactose), table sugar (sucrose), or a type of sugar found in honey and fruits (fructose).

- Truly refractory celiac disease that is not responding to a gluten-free diet.

Refractory celiac disease

In rare instances, the intestinal injury of celiac disease doesn't respond to a strict gluten-free diet. This is known as refractory celiac disease. If you still have symptoms after following a gluten-free diet for 6 months to 1 year, you should talk to your health care team to see if you need further testing to look for explanations for your symptoms.

Diagnosis

Many people with celiac disease don't know they have it. Two blood tests can help diagnose it:

- Serology testing looks for antibodies in your blood. Elevated levels of certain antibody proteins indicate an immune reaction to gluten.

- Genetic testing for human leukocyte antigens (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8) can be used to rule out celiac disease.

It's important to be tested for celiac disease before trying a gluten-free diet. Eliminating gluten from your diet might make the results of blood tests appear in the standard range.

If the results of these tests indicate celiac disease, one of the following tests will likely be ordered:

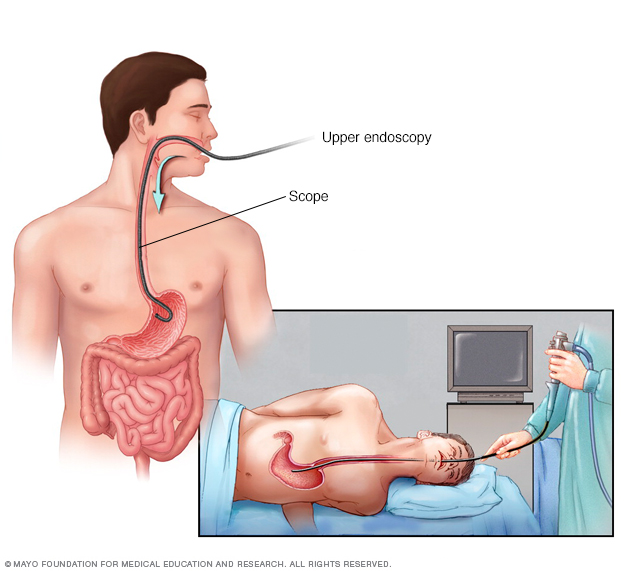

- Endoscopy. This test uses a long tube with a tiny camera that's put into your mouth and passed down your throat. The camera enables the practitioner to view your small intestine and take a small tissue sample, called a biopsy, to analyze for damage to the villi.

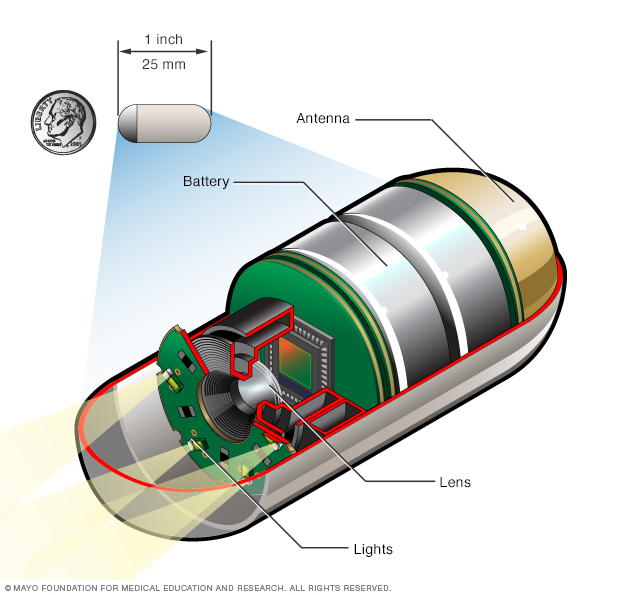

- Capsule endoscopy. This test uses a tiny wireless camera to take pictures of your entire small intestine. The camera sits inside a vitamin-sized capsule, which you swallow. As the capsule travels through your digestive tract, the camera takes thousands of pictures that are transmitted to a recorder. This test is used in some situations where an exam of the entire or end of the small intestine is desired.

If you might have dermatitis herpetiformis, your health care professional may take a small sample of skin tissue to examine under a microscope.

If you're diagnosed with celiac disease, additional testing may be recommended to check your nutritional status. This includes levels of vitamins A, B-12, D and E, as well as mineral levels, hemoglobin and liver enzymes. Your bone health also may be checked with a bone density scan.

During an upper endoscopy, a healthcare professional inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera down the throat and into the esophagus. The tiny camera provides a view of the esophagus, stomach and the beginning of the small intestine, called the duodenum.

A capsule endoscopy procedure involves swallowing a tiny camera that's about the size of a large vitamin pill. The capsule contains lights to light up the digestive system, a camera to take images and an antenna that sends those images to a recorder worn on a belt.

Treatment

A strict, lifelong gluten-free diet is the only way to manage celiac disease. Besides wheat, foods that contain gluten include:

- Barley.

- Bulgur.

- Durum.

- Farina.

- Graham flour.

- Malt.

- Rye.

- Semolina.

- Spelt (a form of wheat).

- Triticale.

A dietitian who works with people with celiac disease can help you plan a healthy gluten-free diet. Even trace amounts of gluten in your diet can be damaging, even if they don't cause symptoms.

Gluten can be hidden in foods, medicines and nonfood products, including:

- Modified food starch, preservatives and food stabilizers.

- Prescription and over-the-counter medications.

- Vitamin and mineral supplements.

- Herbal and nutritional supplements.

- Lipstick products.

- Toothpaste and mouthwash.

- Communion wafers.

- Envelope and stamp glue.

- Play dough.

- Certain makeup products.

Removing gluten from your diet will typically reduce inflammation in your small intestine, causing you to feel better and eventually heal. Children tend to heal more quickly than adults.

Vitamin and mineral supplements

If your anemia or nutritional deficiencies are severe, supplements may be recommended, including:

- Copper.

- Folic acid.

- Iron.

- Vitamin B-12.

- Vitamin D.

- Vitamin K.

- Zinc.

Vitamins and supplements are usually taken in pill form. If your digestive tract has trouble absorbing vitamins, you might be able to get them by injection.

Follow-up care

Medical follow-up at regular intervals can ensure that your symptoms have responded to a gluten-free diet. Your health care team may monitor your response with blood tests. Nutritional markers also are checked regularly.

For most people with celiac disease, eating a gluten-free diet allows the small intestine to heal. For children, that usually takes 3 to 6 months. For adults, complete healing might take several years.

If you continue to have symptoms or if symptoms recur, you might need an endoscopy with biopsies to determine whether your intestine has healed.

Medications to control intestinal inflammation

If your small intestine is severely damaged or you have refractory celiac disease, steroids may be recommended to control inflammation. Steroids can ease severe symptoms of celiac disease while the intestine heals.

Other drugs, such as azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran) or budesonide (Entocort EC, Uceris), might be used.

Treating dermatitis herpetiformis

If you have this skin rash, a medicine called dapsone may be recommended in addition to a gluten-free diet. Dapsone is taken by mouth. If you take dapsone, you'll need regular blood tests to check for side effects.

Refractory celiac disease

With refractory celiac disease, the small intestine doesn't heal. Refractory celiac disease can be quite serious, and there is currently no proven treatment. If you have refractory celiac disease, you may want to seek medical care at a specialized center.

Lifestyle and home remedies

If you've been diagnosed with celiac disease, you'll need to avoid all foods that contain gluten. Ask your health care team for a referral to a dietitian, who can help you plan a healthy gluten-free diet.

Read labels

Avoid packaged foods unless they're labeled as gluten-free or have no gluten-containing ingredients, including emulsifiers and stabilizers that can contain gluten. In addition to cereals, pastas and baked goods, other packaged foods that can contain gluten include:

- Beers, lagers, ales and malt vinegars.

- Candies.

- Gravies.

- Imitation meats or seafood.

- Processed luncheon meats.

- Rice mixes.

- Salad dressings and sauces, including soy sauce.

- Seasoned snack foods, such as tortilla and potato chips.

- Seitan.

- Self-basting poultry.

- Soups.

Pure oats aren't harmful for most people with celiac disease, but oats can be contaminated by wheat during growing and processing. Ask your health care team if you can try eating small amounts of pure oat products.

Allowed foods

Many basic foods are allowed in a gluten-free diet, including:

- Eggs.

- Fresh meats, fish and poultry that aren't breaded, batter-coated or marinated.

- Fruits.

- Lentils.

- Most dairy products, unless they make your symptoms worse.

- Nuts.

- Potatoes.

- Vegetables.

- Wine and distilled liquors, ciders and spirits.

Grains and starches allowed in a gluten-free diet include:

- Amaranth.

- Buckwheat.

- Corn.

- Cornmeal.

- Gluten-free flours (rice, soy, corn, potato, bean).

- Pure corn tortillas.

- Quinoa.

- Rice.

- Tapioca.

- Wild rice.

Coping and support

It can be difficult, and stressful, to follow a completely gluten-free diet. Here are some ways to help you cope and to feel more in control.

- Get educated and teach family and friends. They can support your efforts in dealing with the disease.

- Follow your health care professional's recommendations. It's critical to eliminate all gluten from your diet.

- Find a support group. You might find comfort in sharing your struggles with people who face similar challenges. Organizations such as the Celiac Disease Foundation, Gluten Intolerance Group, the National Celiac Association and Beyond Celiac can help put you in touch with others who share your challenges.

Preparing for an appointment

You might be referred to a doctor who treats digestive diseases, called a gastroenterologist. Here's some information to help you prepare for your appointment.

What you can do

Until your appointment, continue eating your normal diet. Cutting gluten before you're tested for celiac disease can change the test results.

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, including when they started and whether they've changed over time.

- Key personal information, including major stresses or recent life changes and whether anyone in your family has celiac disease or another autoimmune condition.

- All medications, vitamins or supplements you take, including doses.

- Questions to ask during your appointment.

For celiac disease, questions to ask include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Is my condition temporary or long term?

- What tests do I need?

- What treatments can help?

- Do I need to follow a gluten-free diet?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

You may be asked the following questions:

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Have they been continuous or occasional?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to worsen your symptoms?

- What medications and pain relievers do you take?

- Have you been diagnosed with anemia or osteoporosis?

Last Updated Sep 12, 2023

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use