Meniere's disease

Overview

Meniere's disease is an inner ear problem that can cause dizzy spells, also called vertigo, and hearing loss. Most of the time, Meniere's disease affects only one ear.

Meniere's disease can happen at any age. But it usually starts between the ages of 40 to 60. It's thought to be a lifelong condition. But some treatments can help ease symptoms and lessen how it affects your life long term.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Meniere's disease include:

- Regular dizzy spells. You have a spinning feeling that starts and stops suddenly. Vertigo may start without warning. It usually lasts 20 minutes to 12 hours, but not more than 24 hours. Serious vertigo can cause nausea.

- Hearing loss. Hearing loss in Meniere's disease may come and go, especially early on. Over time, hearing loss can be long-lasting and not get better.

- Ringing in the ear. Ringing in the ear is called tinnitus. Tinnitus is the term for when you have a ringing, buzzing, roaring, whistling or hissing sound in your ear.

- Feeling of fullness in the ear. People with Meniere's disease often feel pressure in the ear. This is called aural fullness.

After a vertigo attack, symptoms get better and might go away for a while. Over time, how many vertigo attacks you have may lessen.

When to see a doctor

See your healthcare provider if you have symptoms of Meniere's disease. Other illnesses can cause these problems. So, it's important to find out what's causing your symptoms as soon as possible.

Causes

The cause of Meniere's disease isn't known. Symptoms of Meniere's disease may be due to extra fluid in the inner ear called endolymph. But it isn't clear what causes this fluid to build up in the inner ear.

Issues that affect the fluid, which might lead to Meniere's disease, include:

- Poor fluid drainage. This may be due to a blockage or irregular ear shape.

- Autoimmune disorders.

- Viral infection.

- Genetics.

Because no single cause has been found, Meniere's disease likely has a combination of causes.

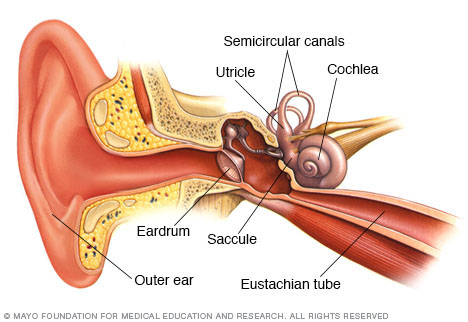

Semicircular canals and otolith organs — called the utricle and saccule — in your inner ear contain fluid and fine, hairlike sensors. These sensory hair cells help you keep your eyes focused on a target when your head is in motion. They also help you keep your balance.

Risk factors

Meniere's disease is most common in people ages 40 to 60. Females may have a slightly higher risk than men.

You may have a higher chance of getting Meniere's disease if someone in your family has had the condition.

You may have a higher risk of Meniere's disease if you have an autoimmune disorder.

Complications

The most difficult complications of Meniere's disease can be:

- Unexpected vertigo attacks.

- Possibly losing your hearing long term.

The disease can happen at any time. This can cause worry and stress.

Vertigo can cause you to lose balance. This can increase your risk of falls and accidents.

Diagnosis

Your healthcare provider does an exam and asks about your health history. A Meniere's disease diagnosis needs to include:

- Two or more vertigo attacks, each lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours, or up to 24 hours.

- Hearing loss proved by a hearing test.

- Tinnitus or a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear.

Meniere's disease can have similar symptoms that are similar to other illnesses. Because of this, your healthcare provider will need to rule out any other conditions you may have.

Hearing assessment

A hearing test is called audiometry. Audiometry looks at how well you hear sounds at different pitches and volumes. It also can test how well you can tell between words that sound the same. People with Meniere's disease often have trouble hearing low frequencies or combined high and low frequencies. They may have typical hearing in the midrange frequencies.

Balance assessment

Between vertigo attacks, balance returns to normal for most people with Meniere's disease. But you might have some ongoing balance problems.

Tests that study how well the inner ear is working include:

- Electronystagmogram or videonystagmography (ENG or VNG). These tests measure balance by studying eye movement. One part of the test looks at eye movement while your eyes follow a target. One part studies eye movement while your head is put in different positions. A third test, called the caloric test, follows eye movement by using temperature changes to trigger a reaction from the inner ear. Your healthcare provider may use warm and cold air or water in the ear for the caloric test.

- Rotary-chair testing. Like a VNG, this test measures how well your inner ear works based on eye movement. You sit in a computer-controlled chair that spins from side to side, which triggers activity in your inner ear.

- Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP) testing. This test uses sound to make parts of the inner ear active. It records how well muscles react to that sound. It may show common changes in the affected ears of people with Meniere's disease.

- Computerized dynamic posturography (CDP). This test shows which part of the balance system you rely on the most and which parts may cause problems. The parts of the balance system include vision, inner ear function or feelings from the skin, muscles, tendons and joints. While wearing a safety harness, you stand barefoot on a platform. Then you keep your balance under different conditions.

- Video head impulse test (vHIT). This test looks at how well the eyes and inner ears work together. vHIT uses video to measure eye reactions to sudden movement. While you focus on a point, your head is turned quickly and unpredictably. If your eyes move off the target when your head is turned, you have a reflex issue.

- Electrocochleography (ECoG). This test looks at how the inner ear reacts to sounds. It can help see if you have inner ear fluid buildup. But this test isn't given only for Meniere's disease.

Tests to rule out other conditions

Lab tests, imaging scans and other tests may be used to rule out conditions. Some other conditions can cause problems like those of Meniere's disease, such as a brain tumor or multiple sclerosis.

Treatment

No cure exists for Meniere's disease. Some treatments can help lessen how bad vertigo attacks are and how long they last. But there are no treatments for permanent hearing loss. Your healthcare provider may be able to suggest treatments that prevent your hearing loss from getting worse.

Medicines for vertigo

Your healthcare provider may prescribe medicines to take during a vertigo attack so that it's less severe:

- Motion sickness medicines. Medicines such as meclizine (Antivert) or diazepam (Valium) may lessen the spinning feeling and help control nausea and vomiting.

- Anti-nausea medicines. Medicines such as promethazine might control nausea and vomiting during a vertigo attack.

- Diuretics and betahistine. These medicines can be used together or alone to improve vertigo. Diuretics lower how much fluid is in the body, which may lower the amount of extra fluid in the inner ear. Betahistines ease vertigo symptoms by improving blood flow to the inner ear.

Long-term medicine use

Your healthcare provider may prescribe a medicine to reduce fluid retention and suggest limiting your salt intake. This helps control the intensity and amount of Meniere's disease symptoms in some people.

Noninvasive therapies and procedures

Some people with Meniere's disease may benefit from procedures that don't include surgery, such as:

- Rehabilitation. If you have balance problems between vertigo attacks, vestibular rehabilitation therapy might improve your balance.

- Hearing aid. A hearing aid in the ear affected by Meniere's disease might improve your hearing. Your healthcare provider can refer you to an ear doctor, also called an audiologist, to talk about the best hearing aids for you.

If conservative treatments aren't successful, your care provider might suggest more-intense treatments.

Middle ear injections

Medicines injected and absorbed in the middle ear may help vertigo symptoms get better. This treatment is done in a care provider's office. Injections can include:

- Gentamicin. This is an antibiotic that's toxic to your inner ear. It works by damaging the sick part of your ear that's causing vertigo. Your healthy ear then takes on the job for balance. But there is a risk of further hearing loss.

- Steroids. Steroids such as dexamethasone also may help control vertigo attacks in some people. Dexamethasone may not work as well as gentamicin. But it's less likely to cause further hearing loss.

Surgery

If vertigo attacks from Meniere's disease are severe and hard to bear and other treatments don't help, surgery might be an option. Procedures include:

- Endolymphatic sac surgery. The endolymphatic sac helps control inner ear fluid levels. This procedure relieves pressure around the endolymphatic sac, which can improve fluid levels. Sometimes, a care provider places a tube inside your ear to drain any extra fluid.

- Labyrinthectomy. With this procedure, the surgeon removes the parts of your ear causing vertigo, which causes complete hearing loss in that ear. This allows your healthy ear to be in charge of sending information about balance and hearing to your brain. Care providers only suggest this procedure if you have poor hearing or total hearing loss in the diseased ear.

- Vestibular nerve section. This procedure involves cutting the vestibular nerve to prevent information about movement from getting to the brain. The vestibular nerve sends balance and movement information from your inner ear to the brain. This procedure usually improves vertigo and keeps hearing in the diseased ear. Most people need medicine that puts them in a sleep-like state, called general anesthesia, and an overnight hospital stay.

Lifestyle and home remedies

You may be able to improve some symptoms of Meniere's disease with self-care tips. Think about trying these tips during a vertigo attack:

- Sit or lie down when you feel dizzy. Avoid things that can make your symptoms worse, such as sudden movement, bright lights, watching television or reading. Try to focus on an object that isn't moving.

- Rest during and after attacks. Don't rush to return to your normal activities. If you feel tired, rest in bed for a short time. Then, slowly get up and move around when you can. This helps the brain readjust your balance signals.

- Prepare for an attack ahead of time. Talk to your healthcare provider about ways you can prepare for a vertigo attack. Talk about medicines you can take for dizziness. And ask about when to go to the hospital or how to prevent injuries, such as a fall.

Lifestyle changes

To avoid causing a vertigo attack, try the following.

- Limit salt. Eating foods and having drinks high in salt can boost the amount of water in your body. For overall health, aim for less than 2,300 milligrams of sodium each day. Experts also suggest spreading your salt intake evenly throughout the day.

- Limit caffeine, alcohol and tobacco. These substances can cause vertigo attacks in some people. Try keeping a journal to track your symptoms and find possible causes.

Coping and support

Meniere's disease can affect your social life, your productivity and the overall quality of your life. Learn all you can about your health problem.

Talk to people who have Meniere's disease, such as in a support group. Group members can give information, resources, support and coping tips. Ask your healthcare provider or therapist about groups in your area or look for information from the Vestibular Disorders Association.

Preparing for an appointment

You're likely to first see your family healthcare provider. Your primary care provider might refer you to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist, a hearing specialist (audiologist), or a nervous system specialist (neurologist).

Here are some tips to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do beforehand, such as fasting before a test. Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, especially those you have during an attack, how long they last and how often they happen.

- Key personal information, including major stresses, recent life changes and family medical history.

- All medicines, vitamins or supplements you take, including the doses.

- Take a family member or friend along, if possible, to help you remember the information you're given.

- Questions to ask your healthcare provider.

For Meniere's disease, some basic questions to ask your healthcare provider include:

- What's likely causing my symptoms?

- What are other possible causes for my symptoms?

- What tests do I need?

- Is my health problem likely temporary or lifelong?

- What's the best option?

- What are other choices to the approach you're suggesting?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there restrictions I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist?

- Are there brochures or other printed material I can have? What websites do you suggest?

Don't wait to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your provider is likely to ask you several questions, such as:

- When did your symptoms start?

- How often do you have symptoms?

- How serious are your symptoms and how long do they last?

- What, if anything, seems to trigger your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Have you had ear problems before? Does anyone in your family have a history of inner ear problems?

Last Updated Jan 3, 2024

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use