Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome

Overview

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a heart condition present at birth. That means it's a congenital heart defect. People with WPW syndrome have an extra pathway for signals to travel between the heart's upper and lower chambers. This causes a fast heartbeat. Changes in the heartbeat can make it harder for the heart to work as it should.

WPW syndrome is fairly rare. Another name for it is preexcitation syndrome.

The episodes of fast heartbeats seen in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome usually aren't life-threatening. But serious heart problems can occur. Rarely, the syndrome may lead to sudden cardiac death in children and young adults.

Treatment of WPW syndrome may include special actions, medicines, a shock to the heart or a procedure to stop the irregular heartbeats.

In Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, an extra electrical pathway between the heart's upper chambers and lower chambers causes a fast heartbeat.

Symptoms

The heart rate is the number of times the heart beats each minute. A fast heart rate is called tachycardia (tak-ih-KAHR-dee-uh).

The most common symptom of Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a heart rate greater than 100 beats a minute.

In WPW syndrome, the fast heartbeat can begin suddenly. It may last a few seconds or several hours. Episodes may occur during exercise or while at rest.

Other symptoms of WPW syndrome may depend on the speed of the heartbeat and the underlying heart rhythm disorder.

For example, the most common irregular heartbeat seen with WPW syndrome is supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). During an episode of SVT, the heart beats about 150 to 220 times a minute, but it can occasionally beat faster or slower.

Some people with WPW syndrome also have a fast and chaotic heart rhythm disorder called atrial fibrillation.

In general, symptoms of WPW syndrome include:

- Rapid, fluttering or pounding heartbeats.

- Chest pain.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Dizziness or lightheadedness.

- Fainting.

- Fatigue.

- Shortness of breath.

- Anxiety.

Symptoms in infants

Infants with WPW may have other symptoms, such as:

- Blue or gray skin, lips and nails. These changes may be harder or easier to see depending on skin color.

- Restlessness or irritability.

- Rapid breathing.

- Poor eating.

Some people with an extra electrical pathway don't have symptoms of a fast heartbeat. This condition is called Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) pattern. It's often discovered by chance during a heart test.

When to see a doctor

Many things can cause a fast heartbeat. It's important to get a prompt diagnosis and care. Sometimes a fast heartbeat isn't a concern. For example, the speed of the heartbeat may increase with exercise.

If you feel like your heart is beating too fast, make an appointment to see a healthcare professional.

Call 911 or your local emergency number if you have any of the following symptoms for more than a few minutes:

- Sensation of a fast or pounding heartbeat.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Chest pain.

Causes

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a heart condition present at birth. That means it's a congenital heart defect. Researchers aren't sure what causes most types of congenital heart defects. WPW syndrome may occur with other congenital heart defects, such as Ebstein anomaly.

Rarely, WPW syndrome is passed down through families. Your healthcare team may call this inherited or familial WPW syndrome. It is associated with a thickened heart muscle, called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

To understand the causes of WPW syndrome, it may be helpful to know how the heart typically beats.

The heart has four chambers.

- The two upper chambers are called the atria.

- The two lower chambers are called the ventricles.

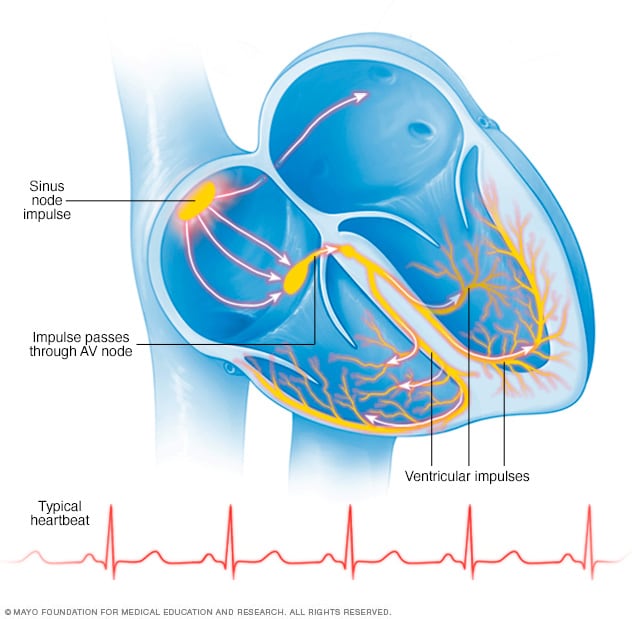

Inside the upper right heart chamber is a group of cells called the sinus node. The sinus node makes the signals that start each heartbeat.

The signals move across the upper heart chambers. Next, the signals arrive at a group of cells called the atrioventricular (AV) node, where they usually slow down. The signals then go to the lower heart chambers.

In a typical heart, this signaling process usually goes smoothly. The resting heart rate is about 60 to 100 beats a minute.

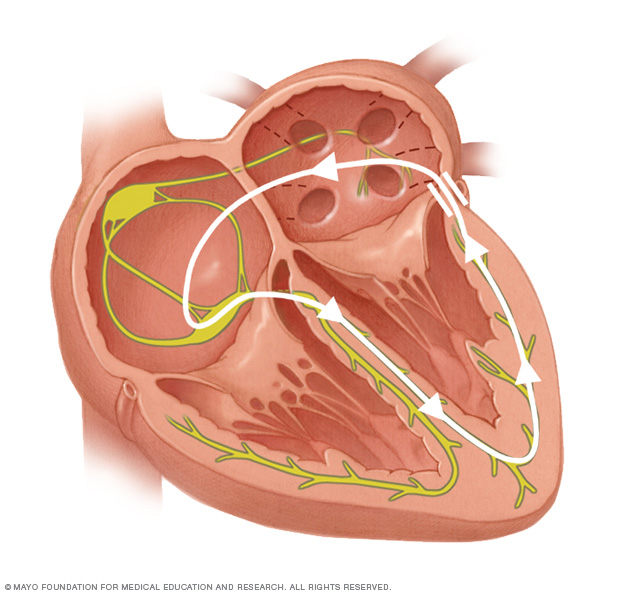

In WPW syndrome, an extra electrical pathway connects the upper and lower heart chambers, allowing heart signals to bypass the AV node. As a result, the heart signals don't slow down. The signals get excited, and the heart rate gets faster. The extra pathway also can cause heart signals to travel backward. This causes an uncoordinated heart rhythm.

In a typical heart rhythm, a tiny cluster of cells at the sinus node sends out an electrical signal. The signal then travels through the atria to the atrioventricular (AV) node and then passes into the ventricles, causing them to contract and pump out blood.

Complications

WPW syndrome has been linked to sudden cardiac death in children and young adults.

Diagnosis

To diagnose Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, a healthcare professional examines you and listens to your heart with a device called a stethoscope. You usually are asked questions about your medical history and symptoms

Tests

Tests may be done to confirm WPW syndrome and look for an underlying cause. Tests may include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick and painless test measures the electrical activity of the heart. Sticky patches called electrodes are placed on the chest and sometimes the arms and legs. Wires connect the electrodes to a computer, which prints or displays the test results. An ECG shows how slow or how fast the heart is beating. A healthcare professional can look for heartbeat patterns that suggest an extra electrical pathway in the heart.

- Holter monitor. This small, portable ECG device records the heart's activity. It's worn for a day or two while you do your regular activities.

- Event recorder. This device is like a Holter monitor, but it records only at certain times for a few minutes at a time. It's typically worn for about 30 days. You usually push a button when you feel symptoms. Some devices automatically record when an irregular heart rhythm is detected.

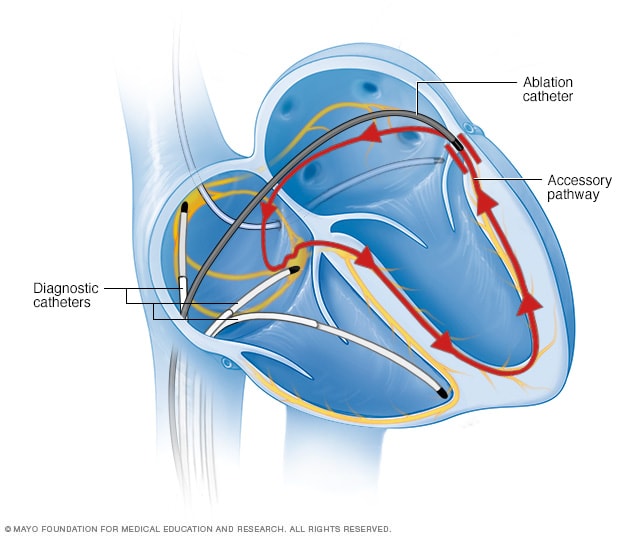

- Electrophysiological (EP) study. An EP study may be done to tell the difference between WPW syndrome and WPW pattern. One or more thin, flexible tubes called catheters are guided through a blood vessel, usually in the groin, to various areas in the heart. Sensors on the tips of the catheters record the heart's electrical patterns. An EP study shows how electrical signals spread through the heart during each heartbeat.

Treatment

Treatment for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome depends on:

- How often symptoms occur.

- How severe the symptoms are.

- The type of irregular heartbeat causing the fast heart rate.

People who have an extra signaling pathway but no symptoms, called WPW pattern, usually don't need treatment.

The goals of WPW syndrome treatment are to:

- Slow a fast heart rate when it occurs.

- Prevent future episodes.

Treatment options may include:

- Vagal maneuvers. These are simple actions that can slow the heartbeat. They include coughing, bearing down as if passing stool and putting an ice pack on the face. Your healthcare team may ask you to do these specific actions during an episode of a fast heartbeat. These actions affect the vagus nerve, which helps control the heartbeat.

- Medicines. If vagal maneuvers don't stop a fast heartbeat, you might need medicines to control the heart rate and restore the heart rhythm. Medicines may need to be given by IV.

- Cardioversion. Paddles or patches on the chest are used to electrically shock the heart and help reset the heart rhythm. Cardioversion is typically used when vagal maneuvers and medicines don't work. It's also possible to do cardioversion with medicines.

- Catheter ablation. In this procedure, a doctor inserts one or more thin, flexible tubes called catheters into an artery, usually in the groin. The doctor guides them to the heart. Sensors on the tip of the catheters use heat or cold energy to create tiny scars in the heart. The scars block irregular electrical signals and restore the heart's rhythm. Catheter ablation may be done at the same time as other heart surgeries.

In catheter ablation, one or more thin, flexible tubes called catheters are passed through a blood vessel and guided to the heart. Sensors on the catheter tips use heat or extreme cold to scar a small area of heart tissue. The scarring blocks faulty electrical signals that cause an irregular heartbeat.

Lifestyle and home remedies

If you have WPW syndrome or any type of heart disease, your healthcare team usually recommends following a heart-healthy lifestyle. Take these steps:

- Do not smoke.

- Eat a healthy diet.

- Get regular exercise.

- Limit or avoid alcohol.

- Avoid caffeine or other stimulants.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Manage emotional stress.

Coping and support

If you have a plan in place to manage an episode of a fast heartbeat, you may feel calmer and more in control when one occurs. Ask your healthcare professional:

- How to take your pulse and what heart rate is best for you.

- When and how to use vagal maneuvers, if appropriate.

- When to make an appointment for a health checkup.

- When to seek emergency care.

Preparing for an appointment

If you have WPW syndrome, you may be referred to a doctor trained in heart problems present at birth. This type of healthcare professional is called a congenital cardiologist.

Because there's often a lot to discuss, it's a good idea to be prepared for your appointment. Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Make a list ahead of time that you can share with your healthcare team. Your list should include details about the following:

- Any symptoms, including those that may seem unrelated to the heart or heartbeat.

- Important personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- All current medicines and their dosages, including vitamins and supplements and medicines bought without a prescription.

- Questions to ask the healthcare team.

Questions to ask your doctor

For WPW syndrome, some basic questions to ask your healthcare team include:

- What is the likely cause of my fast heart rate?

- What tests do I need?

- What treatments can help?

- What are the risks of WPW syndrome?

- How often will I need follow-up appointments?

- Do I need to avoid any activities?

- How will other conditions that I have or medicines I take affect my heart condition?

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional is likely to ask you questions, such as:

- How severe are the symptoms?

- How often does the fast heartbeat occur?

- How long do episodes last?

- Does anything, such as exercise, stress or caffeine, seem to trigger the episodes or make symptoms worse?

- Is there a family history of irregular heartbeats or other heart disease?

Last Updated Dec 13, 2023

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use