Congenital heart disease in adults

Overview

Congenital heart disease is one or more problems with the heart's structure that are present at birth. Congenital means that you're born with the condition. A congenital heart condition can change the way blood flows through the heart.

There are many different types of congenital heart defects. This article focuses on congenital heart disease in adults.

Some types of congenital heart disease may be mild. Others may cause life-threatening complications. Advances in diagnosis and treatment have improved survival for those born with a heart problem.

Treatment for congenital heart disease may include regular health checkups, medicines or surgery. If you have adult congenital heart disease, ask your healthcare professional how often you need a checkup.

Symptoms

Some people born with a heart problem don't notice symptoms until later in life. Symptoms also may return years after a congenital heart defect is treated.

Common congenital heart disease symptoms in adults include:

- Irregular heartbeats, called arrhythmias.

- Blue or gray skin, lips and fingernails due to low oxygen levels. Depending on the skin color, these changes may be harder or easier to see.

- Shortness of breath.

- Feeling tired very quickly with activity.

- Swelling due to fluid collecting inside body tissues, called edema.

When to see a doctor

Get emergency medical help if you have unexplained chest pain or shortness of breath.

Make an appointment for a health checkup if:

- You have symptoms of adult congenital heart disease.

- You received treatment for a congenital heart defect as a child.

Causes

Researchers aren't sure what causes most types of congenital heart disease. They think that gene changes, certain medicines or health conditions, and environmental or lifestyle factors, such as smoking, may play a role.

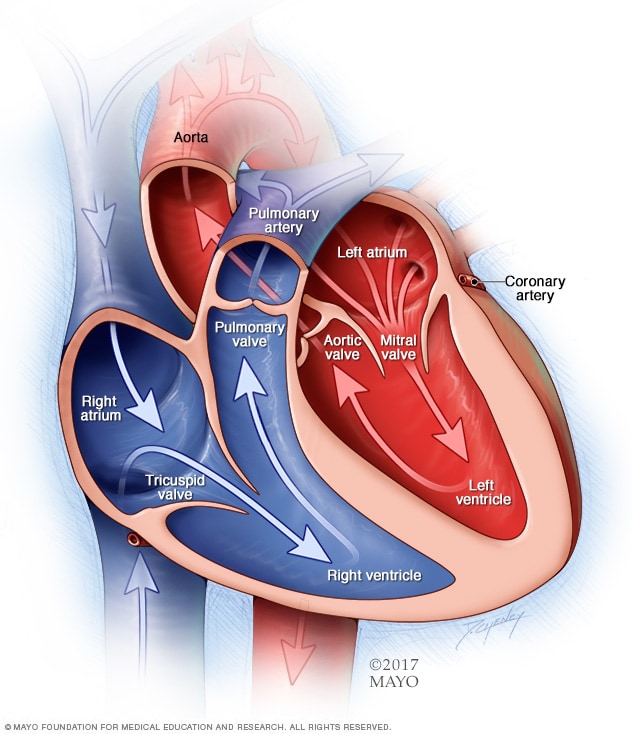

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves help keep blood flowing in the right direction.

Risk factors

Risk factors for congenital heart disease include:

- Genetics. Congenital heart disease appears to run in families, which means it is inherited. Changes in genes have been linked to heart problems present at birth. For instance, people with Down syndrome are often born with heart conditions.

- German measles, also called rubella. Having rubella during pregnancy may affect how the baby's heart grows while in the womb. A blood test done before pregnancy can find out if you're immune to rubella. A vaccine is available for those who aren't immune.

- Diabetes. Having type 1 or type 2 diabetes during pregnancy also may change how the baby's heart grows while in the womb. Gestational diabetes generally doesn't increase the risk of congenital heart disease.

- Medicines. Taking certain medicines during pregnancy can cause congenital heart disease and other health problems present at birth. Medicines linked to congenital heart defects include lithium (Lithobid) for bipolar disorder and isotretinoin (Claravis, Myorisan, others), which is used to treat acne. Always tell your healthcare team about the medicines you take.

- Alcohol. Drinking alcohol while pregnant has been linked to heart conditions in the baby.

- Smoking. If you smoke, quit. Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of congenital heart defects in the baby.

Complications

Complications of congenital heart disease may occur years after the heart condition is treated.

Complications of congenital heart disease in adults include:

- Irregular heartbeats, called arrhythmias. Scar tissue in the heart from surgeries to fix a congenital heart condition can lead to changes in heart signaling. The changes can cause the heart to beat too fast, too slow or irregularly. Some irregular heartbeats may cause stroke or sudden cardiac death if not treated.

- Infection of the lining of the heart and heart valves, called endocarditis. Untreated, this infection can damage or destroy the heart valves or cause a stroke. Antibiotics may be recommended before dental care to prevent this infection. Regular dental checkups are important. Healthy gums and teeth reduce the risk of endocarditis.

- Stroke. Congenital heart disease can let a blood clot pass through the heart and travel to the brain, causing a stroke.

- High blood pressure in the lung arteries, called pulmonary hypertension. Some heart conditions present at birth send more blood to the lungs, causing pressure to build. This eventually causes the heart muscle to weaken and sometimes to fail.

- Heart failure. The heart can't pump enough blood to meet the body's needs.

Adult congenital heart disease and pregnancy

It may be possible to have a successful pregnancy with mild congenital heart disease. A healthcare professional may tell you not to get pregnant if you have complex congenital heart disease.

Before becoming pregnant, talk with your healthcare team about the possible risks and complications. Together you can discuss and plan for any special care needed during pregnancy.

Prevention

Because the exact cause of most congenital heart disease is unknown, it may not be possible to prevent these heart conditions. Some types of congenital heart disease occur in families. If you have a high risk of giving birth to a child with a congenital heart defect, genetic testing and screening may be done during pregnancy.

Diagnosis

To diagnose congenital heart disease in adults, your healthcare professional examines you and listens to your heart with a stethoscope. You are usually asked questions about your symptoms and medical and family history.

Tests

Tests are done to check the heart's health and look for other conditions that may cause similar symptoms.

Tests to diagnose or confirm congenital heart disease in adults include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). This quick test records the electrical activity of the heart. It shows how the heart is beating. Sticky patches with sensors called electrodes attach to the chest and sometimes the arms or legs. Wires connect the patches to a computer, which prints or displays results. An ECG can help diagnose irregular heart rhythms.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the heart and lungs. It can tell if the heart is enlarged or if the lungs have extra blood or other fluid. These could be signs of heart failure.

- Pulse oximetry. A sensor placed on the fingertip records how much oxygen is in the blood. Too little oxygen may be a sign of a heart or lung condition.

-

Echocardiogram. An echocardiogram uses sound waves to create pictures of the beating heart. It shows how blood flows through the heart and heart valves. A standard echocardiogram takes pictures of the heart from outside the body.

If a standard echocardiogram doesn't give as many details as needed, a healthcare professional may do a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). This test gives a detailed look at the heart and the body's main artery, called the aorta. A TEE creates pictures of the heart from inside the body. It's often done to examine the aortic valve.

- Exercise stress tests. These tests often involve walking on a treadmill or riding a stationary bike while the heart activity is checked. Exercise tests can show how the heart responds to physical activity. If you can't exercise, you might be given medicines that affect the heart like exercise does. An echocardiogram may be done during an exercise stress test.

- Heart MRI. A heart MRI, also called a cardiac MRI, may be done to diagnose and look at congenital heart disease. The test creates 3D pictures of the heart, which allows for accurate measurement of the heart chambers.

- Cardiac catheterization. In this test, a thin, flexible tube called a catheter is inserted into a blood vessel, usually in the groin area, and guided to the heart. This test can provide detailed information on blood flow and how the heart works. Certain heart treatments can be done during cardiac catheterization.

Some or all of these tests also may be done to diagnose congenital heart defects in children.

Treatment

A person born with a congenital heart defect can often be treated successfully in childhood. But sometimes, the heart condition may not need repair during childhood or the symptoms aren't noticed until adulthood.

Treatment of congenital heart disease in adults depends on the specific type of heart condition and how severe it is. If the heart condition is mild, regular health checkups may be the only treatment needed.

Other treatments for congenital heart disease in adults may include medicines and surgery.

Medications

Some mild types of congenital heart disease in adults can be treated with medicines that help the heart work better. Medicines also may be given to prevent blood clots or to control an irregular heartbeat.

Surgeries and other procedures

Some adults with congenital heart disease may need a medical device or heart surgery.

- Implantable heart devices. A pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) may be needed. These devices help improve some of the complications that can occur with congenital heart disease in adults.

- Catheter-based treatments. Some types of congenital heart disease in adults can be repaired using thin, flexible tubes called catheters. Such treatments let doctors fix the heart without open-heart surgery. The doctor inserts a catheter through a blood vessel, usually in the groin, and guides it to the heart. Sometimes more than one catheter is used. Once in place, the doctor threads tiny tools through the catheter to fix the heart condition.

- Open-heart surgery. If catheter treatment can't fix congenital heart disease, open-heart surgery may be needed. The type of heart surgery depends on the specific heart condition.

- Heart transplant. If a serious heart condition can't be treated, a heart transplant might be needed.

Follow-up care

Adults with congenital heart disease are at risk of developing complications — even if surgery was done to repair a defect during childhood. Lifelong follow-up care is important. Ideally, a doctor trained in treating adults with congenital heart disease should manage your care. This type of doctor is called a congenital cardiologist.

Follow-up care may include blood and imaging tests to check for complications. How often you need health checkups depends on whether your congenital heart disease is mild or complex.

Coping and support

You may find that talking with other people who have congenital heart disease brings you comfort and encouragement. Ask your healthcare team if there are any support groups in your area.

It also may be helpful to become familiar with your condition. You want to learn:

- The name and details of your heart condition and how it's been treated.

- Symptoms of your specific type of congenital heart disease and when you should contact your healthcare team.

- How often you should have health checkups.

- Information about your medicines and their side effects.

- How to prevent heart infections and whether you need to take antibiotics before dental work.

- Exercise guidelines and work restrictions.

- Birth control and family planning information.

- Health insurance information and coverage options.

Preparing for an appointment

If you were born with a heart condition, make an appointment for a health checkup with a doctor trained in treating congenital heart disease. Do this even if you aren't having any complications. It's important to have regular health checkups if you have congenital heart disease.

What you can do

When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as avoiding food or drinks for a short period of time. Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, if any, including those that may seem unrelated to congenital heart disease, and when they began.

- Important personal information, including a family history of congenital heart defects and any treatment you received as a child.

- All medicines, vitamins or other supplements you take. Include those bought without a prescription. Also include the dosages.

- Questions to ask your healthcare team.

Preparing a list of questions can help you and your healthcare professional make the most of your time together. You might want to ask questions such as:

- How often do I need tests to check my heart?

- Do these tests require any special preparation?

- How do we monitor for complications of congenital heart disease?

- If I want to have children, how likely are they to have a congenital heart defect?

- Are there diet or activity restrictions I need to follow?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage these conditions together?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare team may ask you many questions, including:

- Do your symptoms come and go, or do you have them all the time?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, makes your symptoms worse?

- What's your lifestyle like, including your diet, tobacco use, physical activity and alcohol use?

Last Updated Apr 6, 2024

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use