Diabetes insipidus

Overview

Diabetes insipidus (die-uh-BEE-teze in-SIP-uh-dus) is an uncommon problem that causes the fluids in the body to become out of balance. That prompts the body to make large amounts of urine. It also causes a feeling of being very thirsty even after having something to drink. Diabetes insipidus also is called arginine vasopressin deficiency and arginine vasopressin resistance.

While the terms "diabetes insipidus" and "diabetes mellitus" sound alike, the two conditions are not connected. Diabetes mellitus involves high blood sugar levels. It's a common condition, and it's often called simply diabetes.

There's no cure for diabetes insipidus. But treatment is available that can ease its symptoms. That includes relieving thirst, lowering the amount of urine the body makes and preventing dehydration.

Symptoms

Symptoms of diabetes insipidus in adults include:

- Being very thirsty, often with a preference for cold water.

- Making large amounts of pale urine.

- Getting up to urinate and drink water often during the night.

Adults typically urinate an average of 1 to 3 quarts (about 1 to 3 liters) a day. People who have diabetes insipidus and who drink a lot of fluids may make as much as 20 quarts (about 19 liters) of urine a day.

A baby or young child who has diabetes insipidus may have these symptoms:

- Large amounts of pale urine that result in heavy, wet diapers.

- Bed-wetting.

- Being very thirsty, with a preference for drinking water and cold liquids.

- Weight loss.

- Poor growth.

- Vomiting.

- Irritability.

- Fever.

- Constipation.

- Headache.

- Problems sleeping.

- Vision problems.

When to see a doctor

See your health care provider right away if you notice that you're urinating much more than usual and you're very thirsty on a regular basis.

Causes

Diabetes insipidus happens when the body can't balance its fluid levels in a healthy way.

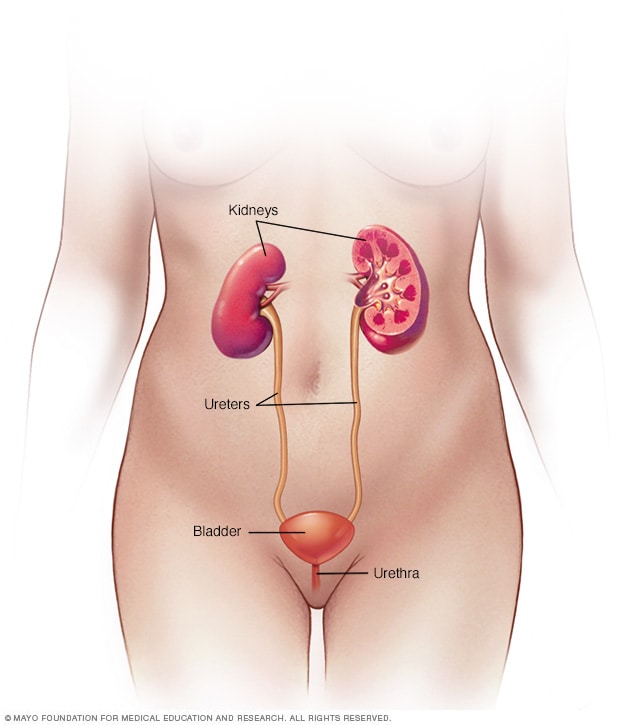

Fluid in the blood is filtered through the kidneys to remove waste. Afterward, most of that fluid is returned to the bloodstream. The waste and a small amount of fluid leave the kidneys as urine. Urine leaves the body after it's temporarily stored in the bladder.

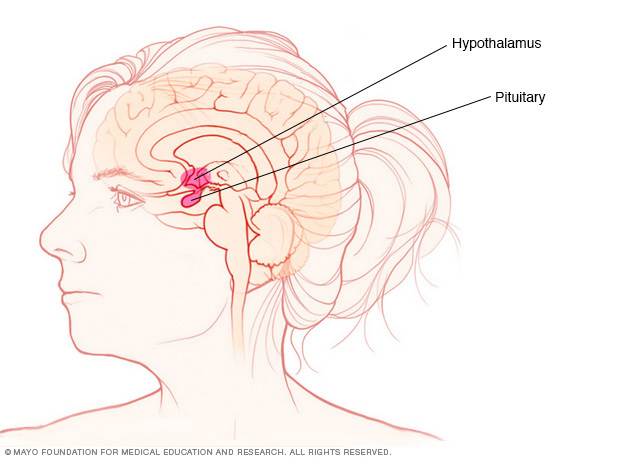

A hormone known as antidiuretic hormone (ADH) — also called vasopressin — is needed to get the fluid that's filtered by the kidneys back into the bloodstream. ADH is made in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. It's then stored in the pituitary gland, a small gland found at the base of the brain. Conditions that cause the brain to make too little ADH or disorders that block the effect of ADH cause the body to make too much urine.

In diabetes insipidus, the body can't properly balance fluid levels. The cause of the fluid imbalance depends on the type of diabetes insipidus.

- Central diabetes insipidus. Damage to the pituitary gland or hypothalamus from surgery, a tumor, a head injury or an illness can cause central diabetes insipidus. That damage affects the production, storage and release of ADH. An inherited disorder may cause this condition too. It also can be the result of an autoimmune reaction that causes the body's immune system to damage the cells that make ADH.

- Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. This happens when there's a problem with the kidneys that makes them unable to properly respond to ADH. That problem may be due to:

- An inherited disorder.

- Certain medicines, including lithium and antiviral medicines such as foscarnet (Foscavir).

- Low levels of potassium in the blood.

- High levels of calcium in the blood.

- A blocked urinary tract or a urinary tract infection.

- A chronic kidney condition.

- Gestational diabetes insipidus. This rare form of diabetes insipidus only happens during pregnancy. It develops when an enzyme made by the placenta destroys ADH in a pregnant person.

- Primary polydipsia. This condition also is called dipsogenic diabetes insipidus. People who have this disorder constantly feel thirsty and drink lots of fluids. It can be caused by damage to the thirst-regulating mechanism in the hypothalamus. It also has been linked to mental illness, such as schizophrenia.

Sometimes no clear cause of diabetes insipidus can be found. In that case, repeat testing over time often is useful. Testing may be able to identify an underlying cause eventually.

The pituitary gland and the hypothalamus are in the brain. They control hormone production.

Your urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The urinary system removes waste from the body through urine. The kidneys are located toward the back of the upper abdomen. They filter waste and fluid from the blood and produce urine. Urine moves from the kidneys through narrow tubes to the bladder. These tubes are called the ureters. The bladder stores urine until it's time to urinate. Urine leaves the body through another small tube called the urethra.

Risk factors

Anyone can get diabetes insipidus. But those at higher risk include people who:

- Have a family history of the disorder.

- Take certain medicines, such as diuretics, that could lead to kidney problems.

- Have high levels of calcium or low levels of potassium in their blood.

- Have had a serious head injury or brain surgery.

Complications

Dehydration

Diabetes insipidus may lead to dehydration. That happens when the body loses too much fluid. Dehydration can cause:

- Dry mouth.

- Thirst.

- Extreme tiredness.

- Dizziness.

- Lightheadedness.

- Fainting.

- Nausea.

Electrolyte imbalance

Diabetes insipidus can change the levels of minerals in the blood that maintain the body's balance of fluids. Those minerals, called electrolytes, include sodium and potassium. Symptoms of an electrolyte imbalance may include:

- Weakness.

- Nausea.

- Vomiting.

- Loss of appetite.

- Confusion.

Diagnosis

Tests used to diagnose diabetes insipidus include:

-

Water deprivation test. For this test, you stop drinking fluids for several hours. During the test, your health care provider measures changes in your body weight, how much urine your body makes, and the concentration of your urine and blood. Your health care provider also may measure the amount of ADH in your blood.

During this test, you may receive a manufactured form of ADH. That can help show if your body is making enough ADH and if your kidneys can respond as expected to ADH.

- Urine test. Testing urine to see if it contains too much water can be helpful in identifying diabetes insipidus.

- Blood tests. Checking the levels of certain substances in the blood, such as sodium, potassium and calcium, can help with a diagnosis and may be useful in identifying the type of diabetes insipidus.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI can look for problems with the pituitary gland or hypothalamus. This imaging test uses a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed pictures of the brain.

- Genetic testing. If other people in your family have had problems with too much urination or have been diagnosed with diabetes insipidus, your health care provider may suggest genetic testing.

Treatment

If you have mild diabetes insipidus, you may only need to drink more water to avoid dehydration. In other cases, treatment typically is based on the type of diabetes insipidus.

-

Central diabetes insipidus. If central diabetes insipidus is caused by a disorder in the pituitary gland or hypothalamus, such as a tumor, that disorder is treated first.

When treatment is needed beyond that, a manufactured hormone called desmopressin (DDAVP, Nocdurna) is used. This medication replaces the missing antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and lowers the amount of urine the body makes. Desmopressin is available as a pill, as a nasal spray and as a shot.

If you have central diabetes insipidus, it's likely that your body still makes some ADH. But the amount can change from day to day. That means the amount of desmopressin that you need also may change. Taking more desmopressin than you need can cause water retention. In some cases, it may cause potentially serious low sodium levels in the blood. Talk to your health care provider about how and when to adjust your dosage of desmopressin.

-

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Because the kidneys don't properly respond to ADH in this form of diabetes insipidus, desmopressin won't help. Instead, your health care provider may advise you to eat a low-salt diet to lower the amount of urine your kidneys make.

Treatment with hydrochlorothiazide (Microzide) may ease your symptoms. Although hydrochlorothiazide is a diuretic — a type of medicine that causes the body to make more urine — it can lower urine output for some people with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

If your symptoms are due to medicines you're taking, stopping those medicines may help. But don't stop taking any medicine without first talking to your health care provider.

- Gestational diabetes insipidus. Treatment for gestational diabetes insipidus involves taking the manufactured hormone desmopressin.

- Primary polydipsia. There is no specific treatment for this form of diabetes insipidus other than lowering the amount of fluids you drink. If the condition is related to a mental illness, treating that may ease symptoms.

Lifestyle and home remedies

If you have diabetes insipidus:

- Prevent dehydration. As long as you take your medicine and have easy access to water, you'll likely be able to prevent serious problems from dehydration. Plan ahead by carrying water with you wherever you go. Keep a supply of medicine with you when you're away from home.

- Wear a medical alert bracelet or carry a medical alert card. If you have a medical emergency, the alert provides information that your health care providers need to give you the right care.

Preparing for an appointment

You're likely to first see your primary care provider. But when you call to set up an appointment, you may be referred to a specialist called an endocrinologist — a physician who focuses on hormone disorders.

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

- Ask about restrictions to follow before your appointment. At the time you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do beforehand. Your health care provider may ask you to stop drinking water the night before the appointment. But do so only if your health care provider asks you to.

- Write down any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment. Be prepared to answer questions about how often you urinate and how much water you drink each day.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of your key medical information, including recent surgeries, the names of all medicines you take and the doses, and any other conditions for which you've recently been treated. Your health care provider also is likely to ask about any recent injuries to your head.

- Take a family member or friend along, if possible. Sometimes it can be hard to remember all the information you get during an appointment. Someone who goes with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your health care provider.

For diabetes insipidus, some basic questions to ask your health care provider include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- What kinds of tests do I need?

- Is my condition likely temporary or will I always have it?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend for me?

- How will you monitor whether my treatment is working?

- Will I need to make any changes to my diet or lifestyle?

- Will I still need to drink a lot of water if I'm taking medicines?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage these conditions together?

- Are there any dietary restrictions I need to follow?

- Are there brochures or other printed material I can take home, or websites you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you questions, including:

- When did your symptoms start?

- How much more are you urinating than usual?

- How much water do you drink each day?

- Do you get up at night to urinate and drink water?

- Are you pregnant?

- Are you being treated, or have you recently been treated for other medical conditions?

- Have you had any recent head injuries, or have you had neurosurgery?

- Has anyone in your family been diagnosed with diabetes insipidus?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

What you can do in the meantime

While you're waiting for your appointment, drink until your thirst is eased, as often as necessary. Avoid activities that might cause dehydration, such as exercise, other physical exertion or spending time in the heat.

Last Updated Apr 5, 2023

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use