Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

Overview

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is a rare heart defect present at birth (congenital). In this condition, the left side of the heart is extremely underdeveloped.

If a baby is born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the left side of the heart can't pump blood well. Instead, the right side of the heart must pump blood to the lungs and to the rest of the body.

Treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome requires medication to prevent closure of the connection (ductus arteriosus) between the right and left sides of the heart. Plus, either surgery or a heart transplant is necessary. Advances in care have improved the outlook for babies born with this condition.

Symptoms

Babies born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome usually are seriously ill soon after birth. Symptoms include:

- Grayish-blue color of the lips and gums (cyanosis)

- Rapid, difficult breathing

- Poor feeding

- Cold hands and feet

- Weak pulse

- Being unusually drowsy or inactive

If the natural connections between the heart's left and right sides (foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus) are allowed to close in the first few days of life in babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, they can go into shock and possibly die.

Signs of shock include:

- Cool, clammy skin that can be pale or lips that can be bluish-gray

- A weak and rapid pulse

- Breathing that may be slow and shallow or very rapid

- Dull eyes that seem to stare

A baby in shock might be conscious or unconscious.

When to see a doctor

Most babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome are diagnosed either before birth or soon after. However, seek medical help if you notice that your baby has any of the symptoms of the condition.

If you think that your baby is in shock, immediately call 911 or your local emergency number.

Causes

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome occurs in the womb when a baby's heart is developing. The cause is unknown. However, having one child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, increases the risk of having another with a similar condition.

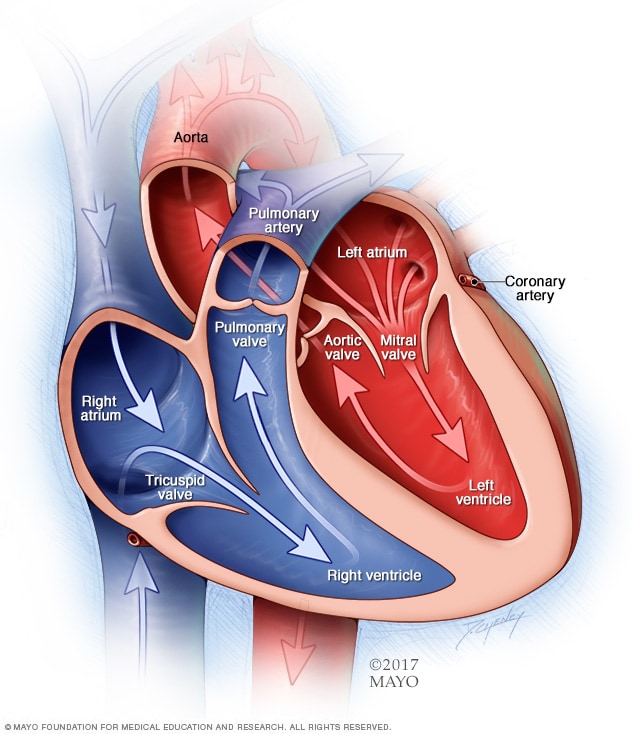

The heart has four chambers, two on the right and two on the left. In doing its basic job — pumping blood through the body — the heart uses its left and right sides for different tasks.

The right side moves blood to the lungs. In the lungs, oxygen enriches the blood, which then moves to the heart's left side. The left side of the heart pumps blood into a large vessel called the aorta, which sends the oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body.

What happens in hypoplastic left heart syndrome

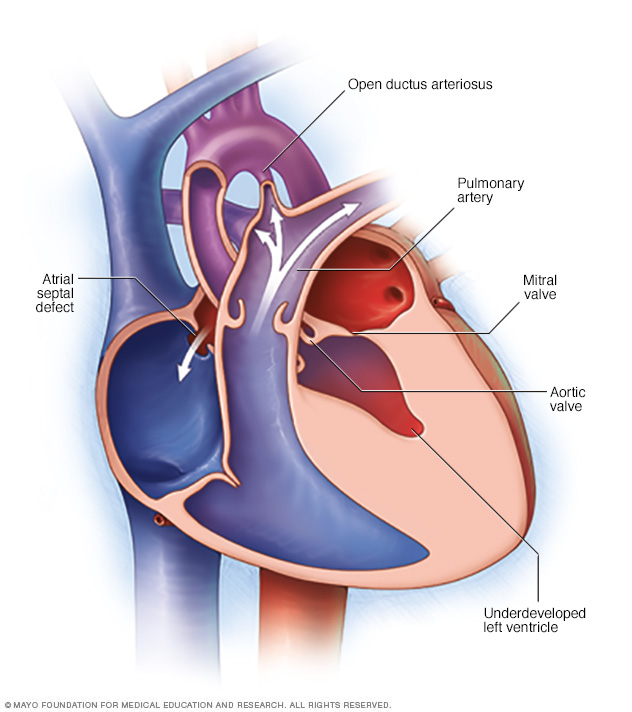

In hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the left side of the heart can't properly supply blood to the body. That's because the lower left chamber (left ventricle) is too small or isn't there. Also, the valves on the left side of the heart (aortic valve and mitral valve) don't work properly, and the main artery leaving the heart (aorta) is smaller than usual.

After birth, the right side of a baby's heart can pump blood both to the lungs and to the rest of the body through a blood vessel that connects the pulmonary artery directly to the aorta (ductus arteriosus). The oxygen-rich blood returns to the right side of the heart through a natural opening (foramen ovale) between the right chambers of the heart.

When the ductus arteriosus and the foramen ovale close — which they usually do after the first day or two of life — the right side of the heart has no way to pump blood to the body. Babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome need medication to keep these connections open and keep blood flowing to the body until they have heart surgery.

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves are gates at the chamber openings. They keep blood flowing in the right direction.

In this condition, the left side of the heart — including the aorta, the aortic valve, the left ventricle and the mitral valve — doesn't develop as it should (hypoplastic). As a result, the body doesn't receive enough oxygen-rich blood.

Risk factors

People who have a child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome have a higher risk of having another baby with this or a similar condition.

There are no other clear risk factors for hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Complications

With proper treatment, many babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome survive. But most have complications later, which may include:

- Tiring easily during sports or other exercise

- Heart rhythm problems (arrhythmias)

- Fluid buildup in the lungs, abdomen, legs and feet (edema)

- Not growing well

- Developing blood clots that may lead to a pulmonary embolism or stroke

- Developmental problems related to the brain and nervous system

- Need for additional heart surgery or a heart transplant

Prevention

There's no way to prevent hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Before getting pregnant, people with a family history of heart defects or who have a child with a congenital heart defect might want to meet with a genetic counselor and a cardiologist who treats congenital heart defects.

Diagnosis

Before birth

It's possible for a baby to be diagnosed with hypoplastic left heart syndrome in the womb. A routine ultrasound exam during the second trimester of pregnancy might show the condition.

After birth

A baby with grayish-blue lips or trouble breathing at birth might have a heart defect, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Other possible symptoms of a heart problem are a heart murmur, which is a sound caused by rushing blood flow that can be heard through a stethoscope.

An echocardiogram can diagnose hypoplastic left heart syndrome. This test uses sound waves that bounce off the baby's heart to produce moving images that show on a video screen.

For babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the echocardiogram shows a small left ventricle and aorta. The echocardiogram might also show issues with heart valves.

Because this test can track blood flow, it shows blood moving from the right ventricle into the aorta. And an echocardiogram can identify other heart conditions, such as an atrial septal defect.

Treatment

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is treated through several surgical procedures or a heart transplant. Your child's health care provider will discuss treatment options with you.

If the diagnosis is made before birth, care providers usually recommend delivery at a hospital with a cardiac surgery center.

Options to help manage a baby's condition before surgery or transplant include:

- Medication. The medication alprostadil (Prostin VR Pediatric) helps widen the blood vessels and keeps the ductus arteriosus open.

- Breathing assistance. Babies who have trouble breathing might need help from a breathing machine (ventilator).

- Intravenous fluids. A baby might receive fluids through a tube inserted into a vein.

- Feeding tube. Babies who have trouble feeding or who tire while feeding can be fed through a feeding tube.

- Atrial septostomy. This procedure creates or enlarges the opening between the heart's upper chambers to allow more blood flow from the right atrium to the left atrium. This is done if the foramen ovale closes or is too small. Babies who already have an opening (atrial septal defect) might not need this procedure.

Surgeries and other procedures

Children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome will likely need several surgeries. Surgeons perform these procedures to create separate pathways to get oxygen-rich blood to the body and oxygen-poor blood to the lungs. The procedures are done in three stages.

-

Norwood procedure. This surgery is usually done within the first two weeks of life. There are several ways to do this procedure.

Surgeons reconstruct the aorta and connect it to the heart's lower right chamber. Surgeons insert a tube (shunt) that connects the aorta to the arteries leading to the lungs (pulmonary arteries), or they place a shunt that connects the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries. This allows the right ventricle to pump blood to both the lungs and the body.

In some cases, a mixed procedure is done. Surgeons implant a stent in the ductus arteriosus to maintain the opening between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. Bands placed around the pulmonary arteries reduce blood flow to the lungs and create an opening between the atria of the heart.

After the Norwood procedure, a baby's skin will still be discolored because oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood continue to mix within the heart. Once a baby successfully passes through this stage of treatment, the odds of survival can increase.

-

Bidirectional Glenn procedure. This procedure is generally the second surgery. It's done when a child is between 3 and 6 months of age. It involves removing the first shunt and connecting one of the large veins that returns blood to the heart (the superior vena cava) to the pulmonary artery. If surgeons previously performed a hybrid procedure, they'll follow additional steps during this procedure.

This procedure reduces the work of the right ventricle by allowing it to pump blood mainly to the aorta. It also allows most of the oxygen-poor blood returning from the body to flow directly into the lungs without a pump.

After this procedure, all the blood returning from the upper body is sent to the lungs, so blood with more oxygen is pumped to the aorta to supply organs and tissues throughout the body.

-

Fontan procedure. This surgery is usually done when a child is between 18 months and 4 years of age. The surgeon creates a path for the oxygen-poor blood in one of the blood vessels that returns blood to the heart (the inferior vena cava) to flow directly into the pulmonary arteries. The pulmonary arteries then send the blood into the lungs.

The Fontan procedure allows the rest of the oxygen-poor blood returning from the body to flow to the lungs. After this procedure, there's little mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood in the heart. So the skin will no longer look discolored.

- Heart transplant. Another surgical option is a heart transplant. However, the number of hearts for transplant is limited, so this option is not used as often. Children who have heart transplants need medications throughout life to prevent rejection of the donor heart.

Follow-up care

After surgery or a transplant, a baby needs lifelong care with a cardiologist trained in congenital heart diseases. Some medications might be needed for heart function. Various complications can occur over time and might require further treatment or other medications.

The child's cardiologist will decide whether the child needs to take preventive antibiotics before certain dental or other procedures to prevent infections. Some children might also need to limit physical activity.

Follow-up care for adults

Adult care requires a cardiologist trained in congenital heart disease in adults. Recent advances in surgical care have allowed children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome to grow into adulthood. So it's not yet clear what challenges an adult with the condition might face. Adults need regular, lifelong follow-up care to watch for changes in the condition.

People considering pregnancy should discuss pregnancy risks and birth control options with their health care providers. Having this condition increases the risk of cardiovascular problems during pregnancy, the risk of miscarriage and the risk of having a baby with congenital heart disease.

Coping and support

It can be challenging to live with hypoplastic left heart syndrome or to care for a baby with the condition. Here are some strategies that might help:

-

Seek support. Ask family members and friends for help. Caregivers need breaks. Talk with your child's cardiologist about support groups and other types of assistance.

If you're a teen or an adult with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, ask your health care provider if there are support groups for adults with congenital heart conditions. It can be helpful to talk to other people who share your challenges.

-

Keep health records. Write down your or your baby's diagnosis, medications, surgery and other procedures and the dates they were performed. Include the name and phone number of the cardiologist, emergency contact numbers for health care providers and hospitals, and other important information. Include a copy of the report from the surgeon in the records.

This information will help you keep track of the care received. It will be useful for care providers who don't know the complex health history. This information is also helpful as your child moves from pediatric care to adult cardiology care.

-

Talk about your concerns. Talk with your child's cardiologist about which activities are best for your child. If some are off-limits, encourage your child in other pursuits rather than focusing on what can't be done.

If other issues about your child's health concern you, discuss them with your child's cardiologist too. If you are an adult with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, ask your care provider about activities you can do. Talk about your concerns.

Last Updated Aug 12, 2022

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use