Uterine polyps

Overview

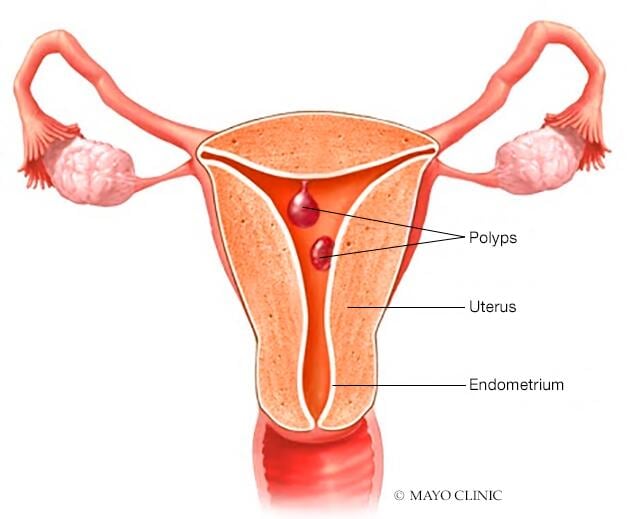

Uterine polyps are growths attached to the inner wall of the uterus that expand into the uterus. Uterine polyps, also known as endometrial polyps, form as a result of cells in the lining of the uterus (endometrium) overgrowing. These polyps are usually noncancerous (benign), although some can be cancerous or can turn into cancer (precancerous polyps).

Uterine polyps range in size from a few millimeters — no larger than a sesame seed — to several centimeters — golf-ball-size or larger. They attach to the uterine wall by a large base or a thin stalk.

There can be one or many uterine polyps. They usually stay within the uterus, but they can slip through the opening of the uterus (cervix) into the vagina. Uterine polyps are most common in people who are going through or have completed menopause. But younger people can get them, too.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of uterine polyps include:

- Vaginal bleeding after menopause.

- Bleeding between periods.

- Frequent, unpredictable periods whose lengths and heaviness vary.

- Very heavy periods.

- Infertility.

Some people have only light bleeding or spotting; others are symptom-free.

When to see a doctor

Seek medical care if you have:

- Vaginal bleeding after menopause.

- Bleeding between periods.

- Irregular menstrual bleeding.

Causes

Hormonal factors appear to play a role. Uterine polyps are estrogen-sensitive, meaning they grow in response to estrogen in the body.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing uterine polyps include:

- Being perimenopausal or postmenopausal.

- Being obese.

- Taking tamoxifen, a drug therapy for breast cancer.

- Taking hormone therapy for menopause symptoms.

Complications

Uterine polyps might be associated with infertility. If you have uterine polyps and you're unable to have children, removal of the polyps might allow you to become pregnant, but the data are inconclusive.

Diagnosis

The following tests might be used to diagnose uterine polyps:

-

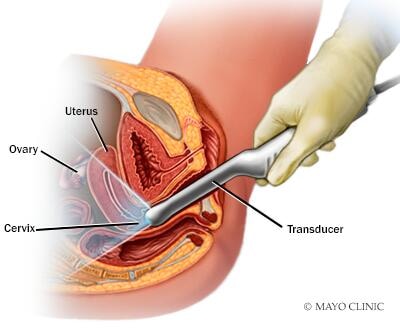

Transvaginal ultrasound. A slender, wandlike device placed in the vagina emits sound waves and creates an image of the uterus, including its insides. A polyp might be clearly present or there might be an area of thickened endometrial tissue.

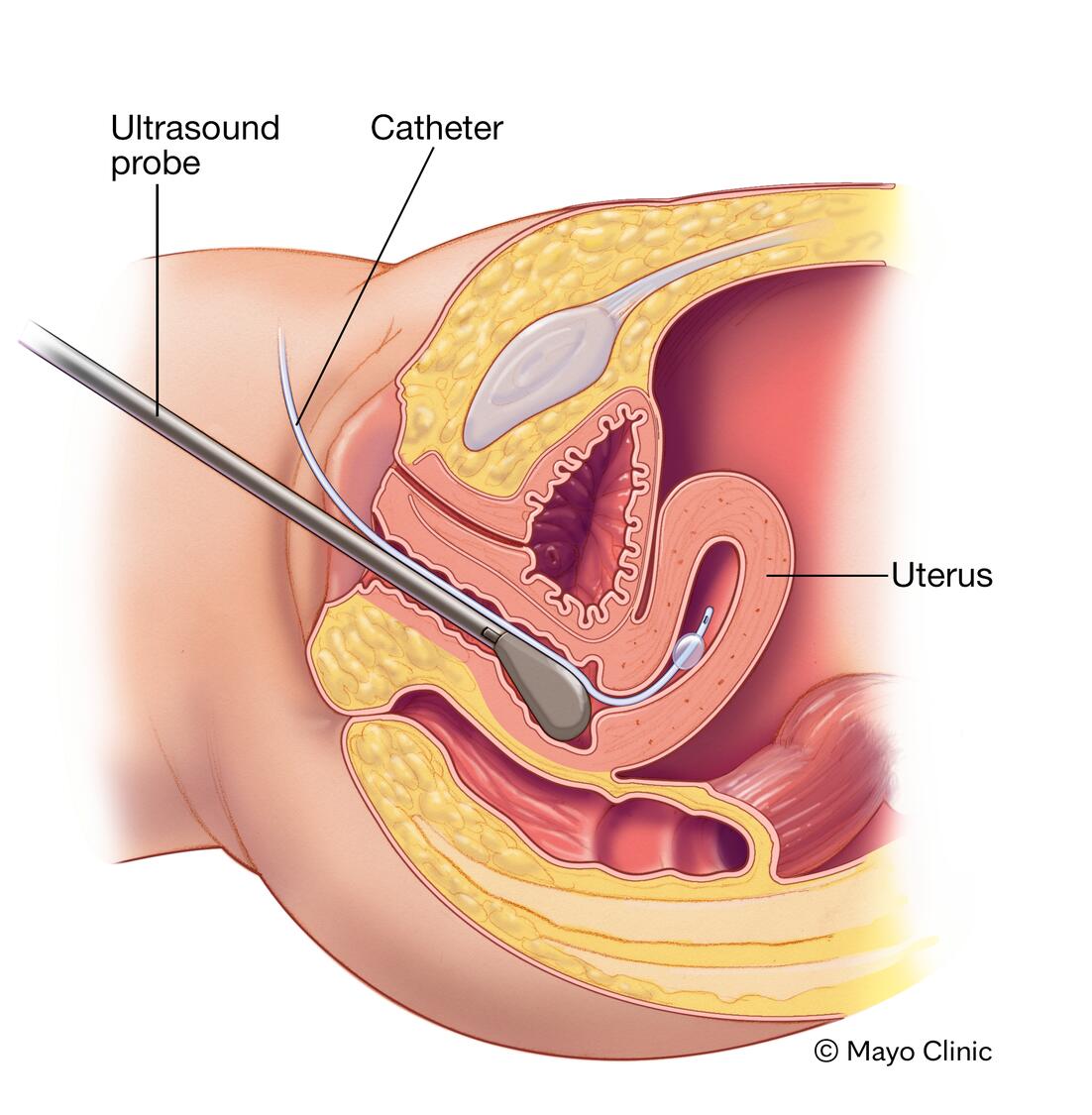

A related procedure, known as hysterosonography (his-tur-o-suh-NOG-ruh-fee) — also called sonohysterography (son-oh-his-tur-OG-ruh-fee) — involves having salt water (saline) injected into the uterus through a small tube placed through the vagina and cervix. The saline expands the uterus, which gives a clearer view of the inside of the uterus during the ultrasound.

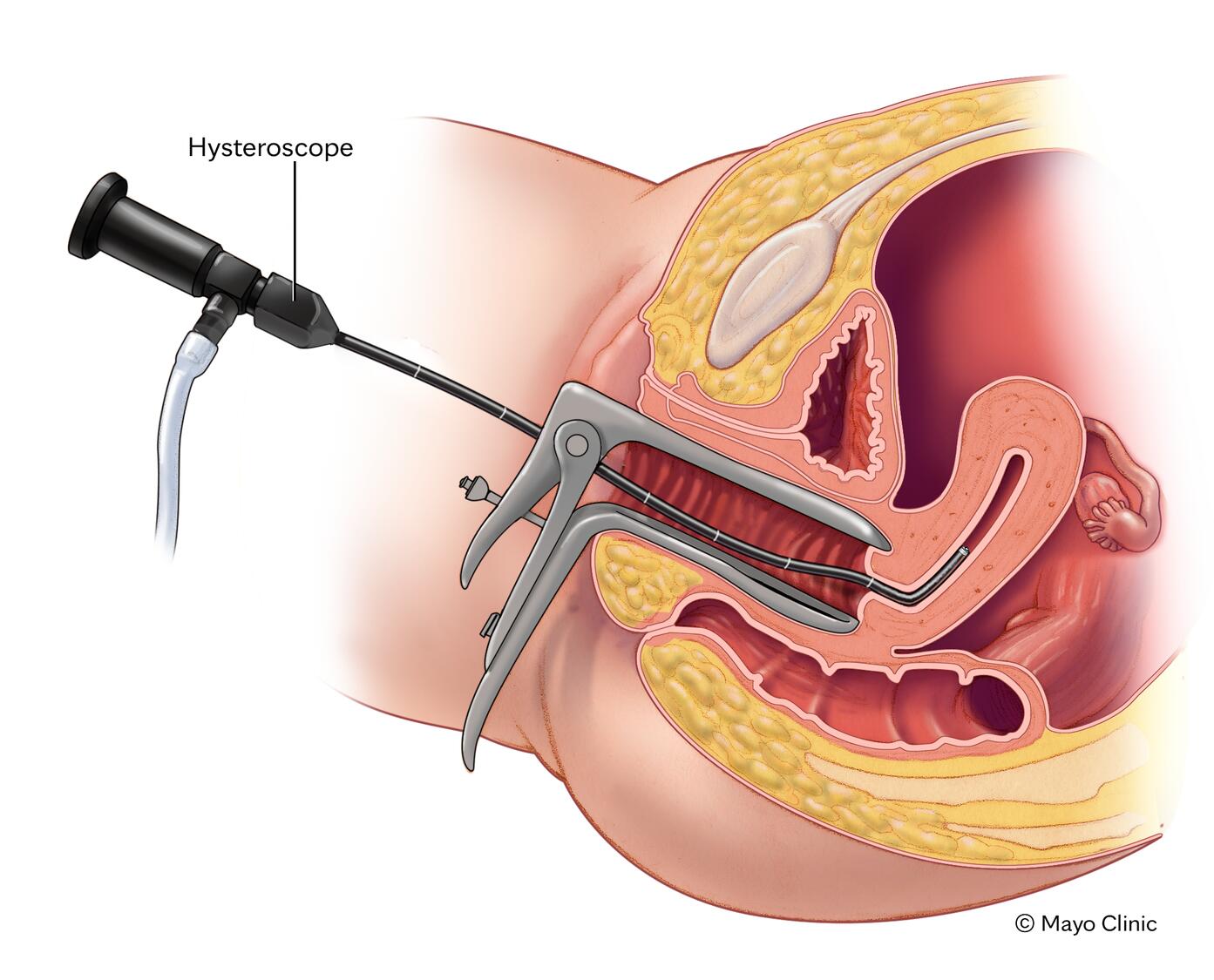

- Hysteroscopy. This involves inserting a thin, flexible, lighted telescope (hysteroscope) through the vagina and cervix into the uterus. Hysteroscopy allows for viewing the inside of the uterus.

- Endometrial biopsy. A suction catheter inside the uterus collects a specimen for lab testing. Uterine polyps might be confirmed by an endometrial biopsy, but the biopsy could also miss the polyp.

Most uterine polyps are benign. This means that they're not cancer. But, some precancerous changes of the uterus, called endometrial hyperplasia, or uterine cancers appear as uterine polyps. A tissue sample of the removed polyp is analyzed for signs of cancer.

Treatment

Treatment for uterine polyps might involve:

- Watchful waiting. Small polyps without symptoms might resolve on their own. Treatment of small polyps is unnecessary for those who aren't at risk of uterine cancer.

- Medication. Certain hormonal medications, including progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, may lessen symptoms of the polyp. But taking such medications is usually a short-term solution at best — symptoms typically recur once the medicine is stopped.

- Surgical removal. During hysteroscopy, instruments inserted through the device used to see inside the uterus (hysteroscope) make it possible to remove polyps. The removed polyp will likely be sent to a lab for examination.

If a uterine polyp contains cancer cells, your provider will talk with you about the next steps in evaluation and treatment.

Rarely, uterine polyps can recur. If they do, they need more treatment.

Preparing for your appointment

Your first appointment will likely be with your primary care provider or a gynecologist. Have a family member or friend go with you, if possible. This can help you remember the information you receive.

What you can do

Make a list of the following:

- Your symptoms, even those you don't think are related, and when they began.

- All medications, vitamins and supplements you take, including doses.

- Questions to ask your provider.

For uterine polyps, some basic questions to ask include:

- What could be causing my symptoms?

- What tests might I need?

- Are medications available to treat my condition?

- Under what circumstances do you recommend surgery?

- Could uterine polyps affect my ability to become pregnant?

- Will treatment of uterine polyps improve my fertility?

- Can uterine polyps be cancerous?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Some questions your provider might ask include:

- How often do you have symptoms?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- Does anything seem to make your symptoms worse?

- Have you been treated for uterine polyps or cervical polyps before?

- Have you had fertility problems? Do you want to become pregnant?

- Does your family have a history of breast, colon or endometrial cancer?

Last Updated Nov 15, 2022

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use