Vertebral tumor

Overview

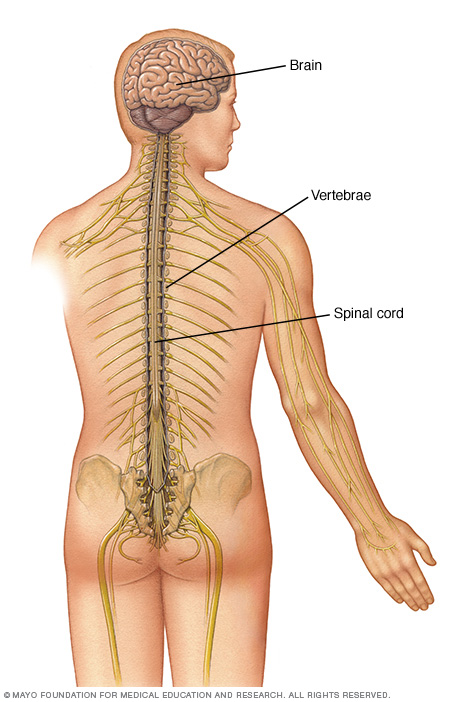

A vertebral tumor is a type of spinal tumor affecting the bones or vertebrae of the spine. Spinal tumors that begin within the spinal cord or the covering of the spinal cord (dura) are called spinal cord tumors.

Tumors that affect the vertebrae have often spread (metastasized) from cancers in other parts of the body. But there are some types of tumors that start within the bones of the spine, such as chordoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, plasmacytoma and Ewing's sarcoma.

A vertebral tumor can affect neurological function by pushing on the spinal cord or nerve roots nearby. As these tumors grow within the bone, they may also cause pain, vertebral fractures or spinal instability.

Whether cancerous or not, a vertebral tumor can be life-threatening and cause permanent disability.

There are many treatment options for vertebral tumors, including surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, medications or sometimes just monitoring the tumor.

Types of vertebral tumors

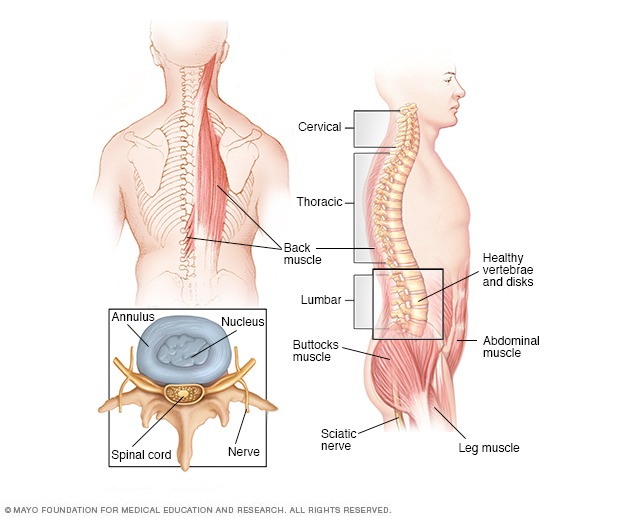

Your spine is made up of small bones (vertebrae) stacked on top of one another that enclose and protect the spinal cord and its nerve roots.

Vertebral tumors are classified according to their location in the spine or vertebral column. Vertebral tumors are also known as extradural tumors because they occur outside the spinal cord itself.

Most tumors that affect the vertebrae have spread (metastasized) to the spine from another place in the body — often the prostate, breast, lung or kidney. Multiple myeloma is a type of cancer that often metastasizes to the spine. Although the original (primary) cancer is usually diagnosed before back problems develop, back pain may be the first symptom of disease in people with metastatic vertebral tumors.

Tumors that begin in the bones of the spine (primary tumors) are far less common. Plasmacytoma is one type of primary vertebral tumor.

Other tumors, such as osteoid osteomas, osteoblastomas and hemangiomas, also can develop in the bones of the spine.

The spinal cord is housed within the spinal canal, a hollow chamber within the vertebrae (spinal canal). It extends from the base of the skull to the lower back.

The spinal anatomy of a typical adult

Symptoms

Vertebral tumors can cause different signs and symptoms, especially as tumors grow. The tumors may affect your spinal cord or the nerve roots, blood vessels, or bones of your spine. Vertebral tumor signs and symptoms may include:

- Pain at the site of the tumor due to tumor growth

- Back pain, often radiating to other parts of your body

- Back pain that's worse at night

- Loss of sensation or muscle weakness, especially in your arms or legs

- Difficulty walking, sometimes leading to falls

- Feeling less sensitive to cold, heat and pain

- Loss of bowel or bladder function

- Paralysis, which may be mild or severe, and can strike in different areas throughout the body

Spinal tumors progress at different rates depending on the type of tumor.

When to see a doctor

There are many causes of back pain, and most back pain isn't caused by a tumor. But because early diagnosis and treatment are important for vertebral tumors, see your doctor about your back pain if:

- It's persistent and progressive

- It's not activity related

- It gets worse at night

- You have a history of cancer and develop new back pain

- You have other systemic signs and symptoms of cancer, such as nausea, vomiting or dizziness

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience:

- Progressive muscle weakness or numbness in your legs or arms

- Changes in bowel or bladder function

Causes

Vertebral tumors that begin in the spine are very rare, and it's not clear why they develop. Experts suspect that defective genes play a role. But it's usually not known whether such genetic defects are inherited or simply develop over time. Or, they might be caused by something in the environment, such as exposure to certain chemicals.

Most vertebral tumors are metastatic, which means they have spread from tumors in organs elsewhere in the body. Any type of cancer can travel to the spine, but common tumor spread from the breast, lung and prostate are more likely than others to spread to the spine. Cancers of the bone, such as multiple myeloma, also may spread to the spine.

Vertebral tumors are also more common in people who have a prior history of cancer.

Complications

Both noncancerous and cancerous vertebral tumors can compress spinal nerves, leading to a loss of movement or sensation below the location of the tumor. This can sometimes cause changes in bowel and bladder function. Nerve damage may be permanent.

A vertebral tumor may also damage the bones of the spine and make it unstable, which raises the risk of a sudden fracture or collapse of the spine that could injure the spinal cord.

However, if caught early and treated aggressively, it may be possible to prevent further loss of function and regain nerve function. Depending on its location, a tumor that presses against the spinal cord itself may be life-threatening.

Diagnosis

Vertebral tumors sometimes may be overlooked because their symptoms resemble those of more-common conditions. For that reason, it's especially important that your doctor know your complete medical history and perform both general physical and neurological exams.

If your doctor suspects a vertebral tumor, one or more of the following tests can help confirm the diagnosis and pinpoint the tumor's location:

Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to produce accurate images of your spine, spinal cord and nerves. MRI is usually the preferred test to diagnose vertebral tumors. A contrast agent that helps to highlight certain tissues and structures may be injected into a vein in your hand or forearm during the test.

Some people may feel claustrophobic inside the MRI scanner or find the loud thumping sound it makes disturbing. Earplugs, televisions or headphones can be used to help minimize the noise. Mild sedatives are frequently used to relieve the anxiety of claustrophobia.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. This test uses a narrow beam of radiation to produce detailed images of your spine. Sometimes it may be combined with an injected contrast dye to make abnormal changes in the spinal canal or spinal cord easier to see. CT scan may be used in combination with MRI.

Biopsy. Often, the only way to determine the type of tumor is to examine a small tissue sample (biopsy) under a microscope. The biopsy results will help determine treatment options.

The method used to obtain the biopsy sample can be critical to the success of the overall treatment plan. You should thoroughly discuss the biopsy with your doctor as well as your surgical team to prevent potential complications. In most cases, a radiologist will conduct a fine-needle biopsy to extract a small amount of tissue, usually under the guidance of X-ray or CT imaging.

Treatment

Ideally, the goal of vertebral tumor treatment is to completely get rid of the tumor. But, this might be complicated by the risk of permanent damage to the spinal cord or surrounding nerves. Doctors also must consider your age, overall health, the type of tumor, and whether it is primary or has spread or metastasized to your spine from elsewhere in your body.

Treatment options for most vertebral tumors include:

Monitoring. Some tumors may be discovered before they cause symptoms — often when you're being evaluated for another condition. If small tumors are noncancerous and aren't growing or pressing on surrounding tissues, watching them carefully may be all that's needed.

This is especially true in older adults for whom surgery or radiation therapy may pose special risks. During observation, your doctor will likely recommend periodic CT or MRI scans at an appropriate interval to monitor the tumor.

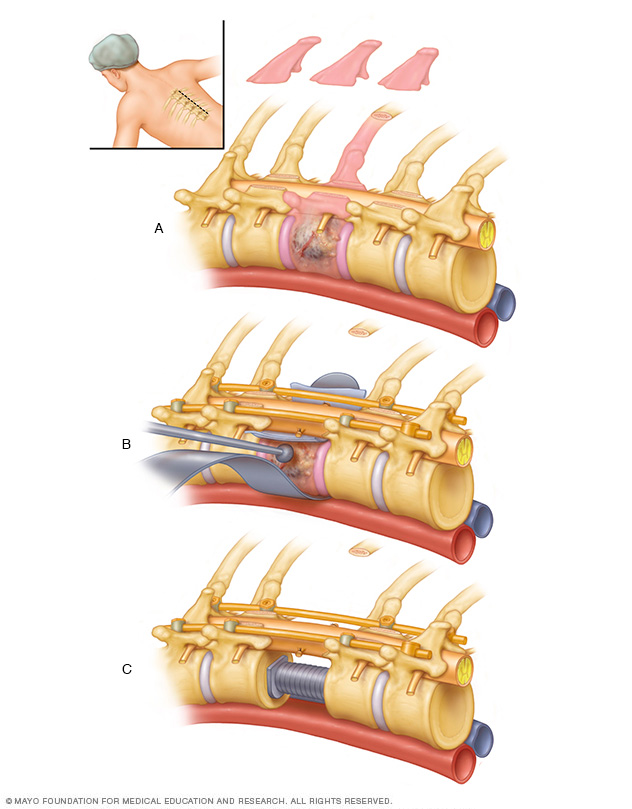

Surgery. This is often the treatment of choice for tumors that can be removed with an acceptable risk of spinal cord or nerve injury.

Newer techniques and instruments allow neurosurgeons to reach tumors that were once considered inaccessible. Sometimes, surgeons may use a high-powered microscope in microsurgery to make it easier to distinguish a tumor from healthy tissue.

Doctors can also monitor the function of the spinal cord and other important nerves during surgery, thus minimizing the chance of their being injured. In some instances, an ultrasound might be used during surgery to break up tumors and remove the fragments.

But even with advances in surgical techniques and technology, not all tumors can be totally removed. Sometimes, surgery might be followed by radiation therapy, chemotherapy or both.

Recovery from spinal surgery may take weeks or longer, depending on the procedure or complications, such as bleeding and damage to nerve tissue.

Radiation therapy. This may be used following an operation to eliminate the remnants of tumors that can't be completely removed, treat inoperable tumors or treat those tumors where surgery is too risky.

It may also be the first line therapy for some vertebral tumors. Radiation therapy may also be used to relieve pain when surgery is too risky.

Medications may help ease some of the side effects of radiation, such as nausea and vomiting.

Sometimes, your radiation therapy regimen may be adjusted to help prevent damage to surrounding tissue from the radiation and improve the treatment's effectiveness. Modifications may range from simply changing the dosage of radiation to using sophisticated techniques such as 3-D conformal radiation therapy.

A specialized type of radiation therapy called proton beam therapy also may be used to treat some vertebral tumors such as chordomas, chondrosarcomas and some childhood cancers when spinal radiation is required. Proton beam therapy can better target radioactive protons at the tumor site without damaging the surrounding tissue as in traditional radiation therapy.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). This treatment, which isn't actually surgery, delivers a high dose of precisely targeted radiation. In SRS, doctors use computers to focus radiation beams on tumors with pinpoint accuracy and from multiple angles.

There are different types of technology used in radiosurgery to stereotactically deliver radiation to treat vertebral tumors.

SRS has certain limits on the size and specific type of the tumors that can be treated. But when appropriate, it's been proved quite effective. Growing research supports its use for the treatment of spinal tumors.

However, there are risks — such as an increased risk of vertebral fractures. Further study is needed to determine the best technique, radiation dose and schedule for SRS in the treatment of vertebral tumors.

Chemotherapy. A standard treatment for many types of cancer, chemotherapy uses medications to destroy cancer cells or stop them from growing. Your doctor can determine whether chemotherapy might be beneficial for you, either alone or in combination with other therapies.

Side effects may include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, increased risk of infection and hair loss.

Other drugs. Because surgery and radiation therapy as well as tumors themselves can cause inflammation inside the spinal cord, doctors sometimes prescribe corticosteroids to reduce the swelling, either following surgery or during radiation treatments.

Although corticosteroids reduce inflammation, they are usually used only for short periods to avoid serious side effects such as muscle weakness, osteoporosis, high blood pressure, diabetes and an increased susceptibility to infection.

Using microsurgical techniques, a tumor is gently teased out of the spinal cord in the cervical spine.

Alternative medicine

Although there aren't any alternative medicines that have been proved to cure cancer, some alternative or complementary treatments may help relieve some of your symptoms.

One such treatment is acupuncture. During acupuncture treatment, a practitioner inserts tiny needles into your skin at precise points. Research shows that acupuncture may be helpful in relieving nausea and vomiting. Acupuncture may also help relieve certain types of pain in people with cancer.

Be sure to discuss the risks and benefits of complementary or alternative treatment that you're thinking of trying with your doctor. Some treatments, such as herbal remedies, could interfere with medicines you're taking.

Coping and support

Learning that you have a vertebral tumor can be overwhelming. But you can take steps to cope after your diagnosis. Consider trying to:

Find out all you can about your specific vertebral tumor. Write down your questions and bring them to your appointments. As your doctor answers your questions, take notes or ask a friend or family member to come along to take notes.

The more you and your family know and understand about your care, the more confident you'll feel when it comes time to make treatment decisions.

Get support. Find someone you can share your feelings and concerns with. You may have a close friend or family member who is a good listener. Or speak with a clergy member or counselor.

Take care of yourself. Choose a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains whenever possible. Check with your doctor to see when you can start exercising again. Get enough sleep so that you feel rested.

Reduce stress in your life by taking time for relaxing activities, such as listening to music or writing in a journal.

Preparing for an appointment

If you have symptoms that are common to vertebral tumors — such as persistent, unexplained back pain, weakness or numbness in your legs, or changes in your bowel or bladder function, call your doctor promptly.

After your doctor examines you, you may be referred to a doctor who is trained to diagnose and treat cancer (oncologist), brain and spinal cord conditions (neurologist, neurosurgeon or spine surgeon), or disorders of the bones (orthopedic surgeon).

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment, and what to expect from the doctor.

What you can do

- Write down any symptoms you've been experiencing and for how long.

- List your key medical information, including all conditions you have and the names of any prescription and over-the-counter medications you're taking.

- Note any family history of brain or spinal tumors, especially in a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling.

- Take a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be difficult to remember all of the information provided to you during an appointment. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your doctor.

Questions to ask your doctor at your initial appointment include:

- What may be causing my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- What kinds of tests do I need? Do these tests require any special preparation?

- What do you recommend for next steps in determining my diagnosis and treatment?

- Should I see a specialist?

Questions to ask an oncologist or neurologist include:

- Do I have a vertebral tumor?

- What type of tumor do I have?

- How will the tumor grow over time?

- What might be the consequences?

- What are the goals of my treatment?

- Am I a candidate for surgery? What are the risks?

- Am I a candidate for radiation? What are the risks?

- Is there a role for chemotherapy?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- If the first treatment isn't successful, what will we try next?

- What is the outlook for my condition?

- Do I need a second opinion?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared to ask your doctor, don't hesitate to ask any additional questions that may come up during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor is likely to ask you a number of questions. Thinking about your answers ahead of time can help you make the most of your appointment. A doctor who sees you for a possible vertebral tumor may ask:

- What are your symptoms?

- When did you first notice these symptoms?

- Have your symptoms gotten worse over time?

- If you have pain, where does the pain seem to start?

- Does the pain spread to other parts of your body?

- Have you participated in any activities that might explain the pain, such as a new exercise or a long stretch of gardening?

- Have you experienced any weakness or numbness in your legs?

- Have you had any difficulty walking?

- Have you had any problems with your bladder or bowel function?

- Have you been diagnosed with any other medical conditions?

- Are you currently taking any over-the-counter or prescription medications?

- Do you have any family history of noncancerous or cancerous tumors?

Last Updated Nov 14, 2020

© 2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use